Tax-benefit microsimulation and income redistribution in Ecuador

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to explore the redistributive effects of taxes and benefits in Ecuador using two different approaches: direct use of reported taxes and benefits in survey data, and use of simulated taxes and benefits. We make use of representative household microdata from ENIGHUR 2011–2012, which contains detailed information on labour and non-labour income, taxes and social insurance contributions, public pensions, social benefits and expenditure, as well as personal and household characteristics. First, ECUAMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for Ecuador is used to simulate cash benefit entitlements, personal income tax and social insurance contribution liabilities, as well as indirect taxes. Then, the redistributive effect of simulated tax-benefit policies is compared to that obtained from taxes, social insurance contributions and benefits taken directly from the data. Our results show that simulated taxes and social insurance contributions capture better the number of taxpayers and aggregate revenue amounts from official statistics, compared to information taken directly from the data. Moreover, using reported data on taxes and social insurance contributions underestimates their redistributive effect, compared to simulated policies. Underreporting of income components in survey data and the difficulty of simulating complex eligibility rules for benefits in microsimulation models are some of the factors driving the differences between the two approaches. Our paper concludes with a discussion of the advantages offered by microsimulation for policy analysis.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the century, and along with the process of dollarization, the tax-benefit system in Ecuador has experienced numerous changes. As part of the reforms introduced in 2008, personal income tax was made more progressive and tax collection became more efficient. The main social assistance benefit in Ecuador, the Human Development Transfer (HDT), has also been made more generous with the monthly payment increasing from USD 30 to USD 35 in 2009, and then to USD 50 since 2013. Over the last decade, a significant decrease in income inequality was also observed, with the Gini coefficient falling from 55.1 in 2007 to 46.6 in 2016 (INEC, 2016).1 From a policy perspective, it is important to assess the redistributive role of tax-benefit instruments with the aim of improving their design in order to strengthen social protection in the country.

The present study compares the redistributive effect of taxes and benefits in Ecuador under two different approaches. The first approach involves using reported information on taxes and benefits from survey data. The second relies on microsimulation techniques to calculate tax-benefit instruments. As stressed by Figari, Iacovou, Skew, and Sutherland (2012), who carry out a similar analysis for selected EU countries, both approaches are subject to different degrees of error. On the one hand, research using data from developed economies has shown that welfare benefits may be underreported in household surveys (Lynn, Jäckle, Jenkins, & Sala, 2012; Meyer, Mok, & Sullivan, 2009). On the other hand, microsimulation models might overestimate means-tested benefits if full take-up is assumed (Figari et al., 2012; Figari, Paulus, & Sutherland, 2015).

Microsimulation models in Ecuador have been developed but limited to the analysis of specific tax components, such as personal income tax, corporate profit tax, and indirect taxes (Ramírez & Oliva, 2008; Ramírez, Cano, & Oliva, 2010; Ramírez, 2010; Ramírez & Carrillo 2012). However, an integrated microsimulation model encompassing both tax and benefit policies is needed if the objective is to perform distributional analysis. This paper makes use of ECUAMOD, the newly developed tax-benefit microsimulation model for Ecuador. ECUAMOD combines detailed country policy rules with representative household microdata from the National Survey of Income and Expenditures of Urban and Rural Households (Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de Hogares Urbanos y Rurales, ENIGHUR) 2011–2012 to simulate cash benefit entitlements, personal income tax and social insurance contribution liabilities, as well as VAT and excise duties for a number of products, for policy years 2011–2017. Our study takes advantage of the availability of reported data on social benefits, taxes and social insurance contributions in ENIGHUR to compare their effect on income inequality and poverty to that of simulated tax-benefit components calculated from ECUAMOD.

The two approaches compared in this paper rely on the quality of the underlying microdata they use. Household survey data is generally affected by income underreporting, misreporting and might fail to capture the top of the market income distribution, particularly so in developing countries (Bustos & Leyva, 2017; CEPAL-IEF, 2014; Figari et al., 2015; Gómez Sabaíni & Rossignolo, 2015). Previous studies have further shown that underreporting might be particularly important in the case of self-employment income (Pissarides & Weber, 1989; Besim & Jenkins, 2005; Hurst, Li, & Pugsley, 2014). Empirical evidence on income underreporting and underrepresentation of top incomes in survey data from Ecuador is scarce. Cano (2014) compares information from household surveys and tax records to show that in 2011 the share of income accruing to the top one per cent accounted for ten per cent according to survey data, whereas it accounted for 12.4 per cent based on tax records. The study shows that underreporting seems to be more prevalent among self-employed individuals and this type of income, together with capital income, represent a higher share of total income at the top of the income distribution in Ecuador. Problems of income underreporting or underrepresentation of top market incomes in survey data would necessarily affect results of tax-benefit microsimulation models based on household surveys. For instance, simulated income taxes or social insurance contributions might underestimate aggregate tax revenue from official sources if the survey fails to capture rich households. Note, however, that information on tax payments and benefit receipts collected in survey data might also suffer from underreporting or misreporting. As such, simulated taxes and benefits might provide a better match against administrative statistics than information reported directly in the survey data, depending of the degree of measurement error of each income component (Figari et al., 2015).

In the case of Ecuador, as in most developing countries, rich household survey data containing detailed information about taxes and cash transfers is scarce. For this reason, research on the redistributive effect of taxes and benefits in Ecuador remains limited. CEPAL-IEF (2014) use household survey data to study the effect of tax-benefit systems on income inequality in Latin America. Results for Ecuador are based on the 2011 National Survey of Urban and Rural Employment, Unemployment and Underemployment (Encuesta Nacional de Empleo, Desempleo y Subempleo, ENEMDUR). Information about cash transfers is taken directly from the data, whereas direct taxes are imputed. According to their results, direct taxes and cash transfers in Ecuador reduce income inequality by 2.8 points, when Gini for disposable income is compared to Gini for market income. Public pensions and cash transfers account for 2 points reduction in inequality, whereas taxes and social insurance contributions account for 0.8 points. More recently, the Commitment to Equity (CEQ) Institute has studied the incidence of taxes and benefits in Latin American countries under a common methodology.2 Lustig (2017) presents a comparative assessment of the impact of fiscal policy on inequality and poverty in Latin America. The results for Ecuador are based on reported information about cash transfers, taxes and social security contributions payments from ENIGHUR 2011–2012 (Llerena, Paul, Llerena Pinto, Saá Daza, & Llerena Pinto, 2015). According to Lustig (2017), the tax-benefit system in Ecuador reduces income inequality by 3.02 points, when Gini for disposable income is compared to Gini for market income.

Distributional analysis based on ECUAMOD differs from previous studies in several respects. First, ECUAMOD systematically applies legislation rules to simulate taxes and benefits, based on the information available in the data. Lustig (2017) uses taxes and benefits reported directly in the data unless the information is not available, in which case these incomes are inferred, predicted or imputed from other sources. CEPAL-IEF (2014) use benefits information from the data but impute direct taxes. Second, contrary to Lustig (2017), our definition of market income does not include imputed rent, as this component is not considered in the calculations of poverty and inequality by the national statistics office in Ecuador. Finally, for Ecuador Lustig (2017) includes in-kind transfers such as free school breakfast, textbooks and uniforms as part of direct transfers (see Llerena et al., 2015). This information is imputed from other sources and not included in our simulations. Differences between our results and those of previous studies are on account of the abovementioned factors.

Our results show that reported social assistance benefits (i.e. the Human Development Transfer) from ENIGHUR data match well the number of recipients and aggregate amounts from official sources, whereas simulated benefits are slightly underestimated due to the difficulty of simulating complex eligibility rules. Reported personal income tax provides a poor representation of the number of taxpayers and aggregate tax revenue relative to tax records, capturing only 22 per cent of tax revenue. ECUAMOD simulations match better the external statistics on personal income tax capturing around 82 per cent of income tax revenue, and highlighting the advantages of microsimulation to calculate income components which are difficult to collect in survey data. Our comparison of inequality and poverty indicators calculated from reported ENIGHUR data and simulated ECUAMOD data shows only minor differences between both approaches, with slightly lower estimates obtained with ECUAMOD simulations. Our results depict, however, a very different picture of the redistributive effect of direct taxes and social insurance contributions depending on the approach used in the analysis. Direct taxes (social insurance contributions) reduce inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, only by 0.3 (0.9) points based on ENIGHUR data, whereas the effect is 1 (1.3) point(s) based on ECUAMOD simulations, which reflects the fact that ECUAMOD simulations capture better the number of taxpayers and tax revenue compared to ENIGHUR data. We discuss potential reasons for the observed discrepancies and highlight the advantages offered by ECUAMOD for distributional analysis and ex-ante policy evaluation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the household survey data used in the analysis and provides detailed information about our tax-benefit microsimulation model. Section 3 presents and discusses the results of the analysis. Finally, Section 4 concludes.

2. Data and methodology

2.1 National survey of income and expenditures of Urban and rural households (ENIGHUR 2011–2012)

ENIGHUR is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey on income and expenditures of households in Ecuador. The aim of the survey is to provide information on the distribution and structure of income and expenditures of Ecuadorean households based on the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the household members (INEC, 2012). The survey is conducted approximately every eight years. The latest ENIGHUR is for years 2011–12 and contains information for 39,617 households and 153,444 individuals. The survey follows a probabilistic two-stage sample design in nine self-represented cities, and a three-stage design in the rest of the country.3 The sampling unit is the dwelling defined as the person or group of people living in the same housing structure (dwelling), sharing meals, and who depend on a common budget. Information about the household and each member of the household occupying the dwelling is collected in the survey.

ENIGHUR contains very detailed income information. Gross employment and self-employment income from principal and secondary occupations are reported, including extra pay, bonuses, inkind income and self-consumption from self-employment activities. Contributions to social security and tax payments are also collected for both, employees and self-employed workers.4 Moreover, detailed information about affiliation to social security is reported, allowing to categorize individuals to specific social security regimes. Cash transfers from social benefits, such as public pensions, the HDT, Joaquín Gallegos Lara transfer and the housing grant are also available. Other sources of income such as income from capital and property, private transfers, remittances, and other rents, are also reported in the data. Finally, detailed data on household expenditures is also available in the survey, as well as information on demographic and socio-economic characteristics of each member of the household.

The present study takes advantage of the availability of reported data on social benefits, taxes and social insurance contributions to compare their effect on income inequality and poverty relative to that of simulated tax-benefit components calculated from ECUAMOD, which is presented in the next section.

2.2 ECUAMOD

Our study makes use of ECUAMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for Ecuador. ECUAMOD has been developed as part of UNU-WIDER’s project on ‘SOUTHMOD-simulating tax and benefit policies for development’ in which tax-benefit microsimulation models have being built for selected developing countries. ECUAMOD and other country models from the SOUTHMOD project have been implemented on the EUROMOD software, which provides a harmonized setting for cross-country comparative analysis on the redistributive effect of tax-benefit policies (see Sutherland & Figari 2013). ECUAMOD combines detailed country-specific coded policy rules with representative household microdata to simulate direct and indirect taxes, social insurance contributions, as well as cash transfers for the household population of Ecuador. ECUAMOD is a static model in the sense that tax-benefit simulations abstract from behavioural reactions of individuals and no adjustments are made for changes in the population composition over time. Simulation results for ECUAMOD have been validated against external statistics (see Jara, Varela, Cuesta, & Amores, 2017).

The underlying microdata used in ECUAMOD comes from ENIGHUR 2011–2012. Adjustments to the data and variables, for the construction of ECUAMOD’s input data, are kept to a minimum. On the one hand, individuals recorded as domestic employees in a household have been dropped, as information about their own household (e.g. number of children, expenditures) is not available. In total, 103 individuals (0.07 per cent of the sample) were dropped from the original sample, leaving us with a sample of 153,341 individuals. No households were dropped and no adjustments to the weights were made as a result of dropping individual observations. On the other hand, ENIGHUR data includes a single variable covering all pension payments. This variable includes contributory pensions, as well as severance pay and alimony for divorce and children. This single variable is disaggregated into five variables in the ECUAMOD database according to the characteristics of the recipients: (i) old-age pension, (ii) disability pension, (iii) survivors’ pension, (iv) severance pay, and (v) alimony payments. In our analysis, the first three variables are considered as part of public pensions, severance pay is included in social benefits and alimony payments are included as part of market income.

ECUAMOD version 1.4 covers policy years 2011–2017 for the purpose of tax-benefit simulations, based on ENIGHUR 2011–2012. To account for time inconsistencies between the input data year and the policy year in the simulations, market incomes and non-simulated tax-benefit variables in the data are adjusted using source-specific updating factors (see Jara et al. 2017). In this study, 2011 policies (as on June 30th) in Ecuador are used for the analysis.

ECUAMOD aims to simulate the main tax and benefit components of household disposable income in Ecuador, where household disposable income is defined as the sum of market income plus government cash transfers of all household members net of income tax and social insurance contributions.5 However, simulation of tax-benefit instruments depends on the relevant information being available in the underlying dataset used in the simulations, in this case ENIGHUR 2011–2012. Instruments which are not simulated are taken directly from the data and included as part of disposable income. The remainder of this section describes briefly the policy instruments simulated in ECUAMOD for year 2011, as well as the underlying assumptions used in the simulations of each income component. Table A.1 in the appendix summarizes the tax and benefit components included in the model, differentiating between simulated and non-simulated components, and provides information about why simulation was not feasible.

2.2.1 Employee social insurance contributions

Social insurance contributions (SICs) in Ecuador are defined according to the sector where the person affiliated with the Ecuadorian Institute of Social Security (Instituto Ecuatoriano de Seguridad Social, IESS) works. ENIGHUR contains information about affiliation to social security for each individual in the data. ECUAMOD therefore simulates SIC payments only for those individuals, who report affiliation to the social security system in the survey.

Employees SICs are simulated for three sectors of work: (a) private sector employees and secular clergy members; (b) bank employees, employees of municipal and decentralized public institutions, notaries, and property and commercial registrars; and (c) civil servants, including public education teachers and employees in the judiciary system, or other. All employees are liable to pay SICs based on their gross employment income. The minimum contribution base equals the minimum wage (USD 264 in 2011) for full-time employees, or a fraction of the minimum wage based on the number of days of work for part-time employees. In 2011, employees were liable to four types of social contributions: pension insurance, rural worker insurance, severance pay insurance, and administrative costs. The total contribution rate was 9.35 per cent or 11.35 per cent depending on the sector of work. Since 2009, pensioners also contribute to social insurance at a rate of 2.76 per cent of their pension income. Social insurance contributions from pensioners are categorised under employee SICs in ECUAMOD.

2.2.2 Self-employed social insurance contributions

Self-employed workers can contribute to SICs on a voluntary basis based on their declared gross self-employment income with specific rates. The minimum contribution base equals the minimum wage. Two categories of workers are considered for the simulation of self-employment SICs: self-employed workers and voluntary affiliated workers. In 2011, self-employed SICs included five types of contributions: pension insurance, health insurance, occupational risk insurance, rural worker insurance, and administrative costs. The total contribution rate for these categories was 17.50 per cent. An additional category of workers included in the simulation of self-employed SICs is rural workers, who are affiliated to the special rural worker social security regime (Seguro Campesino). In order to be member of the rural worker social security regime a person must: (i) have a residency in the rural area or be an artisanal fisherman, (ii) not be affiliated to the general social security regime, (iii) not receive remuneration from an employer, and (iv) not be a permanent employer. The amount of SICs paid by members of the rural worker social security regime is equal to 2.5 per cent of 22.5 per cent of the minimum wage.

2.2.3 Employer social insurance contributions

All employers are liable to pay SICs on gross employment income. Employers are liable to six types of SICs: pension insurance, health insurance, occupational risk insurance, rural worker insurance, severance pay insurance, and administrative costs. The total contribution rate for employers has been fixed at 9.15 per cent or 11.15 per cent depending on the sector of employment of their workers. Employer SICs do not enter in the definition of disposable income in ECUAMOD.

2.2.4 Armed forces and police social insurance contributions

Members of the armed forces or the national police contribute to special regimes of social insurance. Members of the armed forces are affiliated to the Institute of Social Security of the Armed Forces (ISSFA), whereas members of the national police are affiliated to the Institute of Social Security of the National Police (ISSPOL). The information available in the input data for ECUAMOD allows us to distinguish those individuals who are affiliated to these specific regimes. For this reason, in addition to SICs to the IESS, ECUAMOD simulates contributions made by members of the armed forces or the national police. The rate of SICs for members of the ISSFA is 23 per cent, whereas the rate for members of the ISSPOL is 23.10 per cent. ECUAMOD simulates jointly SICs to ISSFA and ISSPOL, assuming a common rate of 23.05 per cent of earnings. This assumption is made due to the fact that the level of detail in the input data for ECUAMOD does not allow distinguishing whether an individual is affiliated to the ISSFA or the ISSPOL. Additionally, ECUAMOD simulates the government contribution to these special regimes at the 26 per cent rate, however, this contribution is not included as part of disposable income in ECUAMOD.

2.2.5 Personal income tax

Personal income tax in Ecuador is assessed at the individual level. The tax base is defined as taxable income minus exemptions, minus deductions. Since 2008, taxable income is composed of gross earnings from labour (employment and self-employment income), plus extra pay, plus utilities participation.6 The main sources of income exempted are income from pensions from the IESS, the 13th and 14th months’ pay, reserve funds, and deductions for old age and disabled persons. Deductions from taxable income are composed of contributions to social security and deductions from personal expenditures, which include expenditure in food, clothing, education, health, and housing.7 The tax schedule applied to the tax base is formed from nine tax bands and rates between 0 and 35 per cent.

In ECUAMOD, personal income tax is simulated under the assumption of full compliance (zero evasion). Simulation of some sort of tax evasion could be included in future versions of the model, based on certain assumptions about people who might be evading tax payments.

2.2.6 Indirect taxes

Since 2000, the VAT rate has been set at 12 per cent.8 Some goods and services considered necessities are taxed at a zero per cent rate, such as food products and basic services like water and electricity. A special consumption tax (Impuesto a los consumos especiales, ICE), which represents a form of excise duty, is also applied to specific products and services, such as alcohol, tobacco products, and automobiles. The rates vary widely with respect to the type of good. In ECUAMOD, indirect taxes are simulated based on information from household expenditures on different types of goods and services, available from the data. The 12 per cent rate is applied to expenditure in goods subject to VAT. ECUAMOD also simulates ICE for four types of goods based on the number of observations in the data for which consumption of these goods is observed. In particular, we simulate ICE for alcoholic drinks including beer, cigarettes, soda drinks, and perfumes.9

2.2.7 Human Development Transfer (Bono de Desarrollo Humano)

The Human Development Transfer (HDT) is a proxy means-tested conditional cash transfer (CCT). Proxy means-tested transfers are common in developing countries and involve evaluating eligibility not in terms of income (means-test) but in terms of a composite index of socio-economic characteristics (proxy means-test). A household is considered eligible for the transfer if their composite index is below a certain threshold. In Ecuador, the proxy means-test is based on the composite index of socio-economic classification of the Social Registry, which is based on a series of variables containing information on household characteristics, characteristics of the head of the household, housing, living conditions, assets, and territory. Three population subgroups are eligible for HDT: (i) families with children younger than 18 years, (ii) elderly adults who do not receive any pension, and (iii) disabled persons. In order to be eligible for HDT, families of children aged 18 years or below need to belong to the poorest population according to the composite index. Elderly adults and disabled persons (with 40 per cent or higher degree of disability) need to be in vulnerability conditions (as defined by the Ministry of Social Development Coordination) and cannot be affiliated with any type of social security institutions.

In 2011, the benefit amount for HDT was USD 35 per month. Since 2013, the amount has been fixed at USD 50 per month (Presidencia de la República, 2009, 2013). Two types of conditionality apply to mothers with children receiving HDT. First, it is required that children aged 6 to 18 years in the household enrol in school and attend at least 90 per cent of the school days in a month. Second, it is required that children below six years in the household attend health centres at least twice per year for medical check-ups.10

In order to simulate eligibility for HDT in ECUAMOD, a pseudo composite index was generated in the input data. Our pseudo index and the official index are likely to have different distributions as they are based on different samples. 11 Therefore, we determine the threshold for eligibility as the value of the pseudo index below which we identify the same number of individuals as the official index.

2.2.8 Transfer Joaquín Gallegos Lara

The transfer Joaquín Gallegos Lara was introduced with the aim of improving living conditions of people with severe disabilities or illness, who are unable to live independently and who live under critical economic conditions (Presidencia de la República 2010: Executive Decree 422). The following categories are eligible for the benefit: (i) individuals with at least 75 per cent level of physical disability or 65 per cent of mental disability; (ii) individuals with catastrophic or rare illnesses, who are not affiliated with or receiving pensions from the social security system; (iii) children below the age of 14 years living with HIV/AIDS; and (iv) orphans. The amount of the benefit is USD 240 per month and it is paid to the person responsible for the care of the individual with a disability or illness. The benefit is not subject to income test.

In ECUAMOD, the transfer Joaquín Gallegos Lara is only partially simulated, meaning that eligibility to the benefit is based on whether individuals are observed receiving the benefit in the data. Full simulation (simulation of eligibility) is not possible because information about the degree of disability is not available in the data.

2.2.9 Non-simulated taxes and benefits

Contributory pensions are included in the concept of disposable income used by ECUAMOD but cannot be simulated due to lack of information on contributory records. The same applies to injury benefit and severance pay. Scholarships cannot be simulated because information on students’ grades is not available in the data. No information on price of properties to be purchased or remodelling costs are available to simulate housing grant. Property and property transfer tax, motor vehicle and wealth tax are taken directly from the data and subtracted in the calculation of disposable income but cannot be simulated due to lack of data on property values, vehicle values and wealth, respectively.

3. Empirical results

This section presents the main findings of our comparison of income distributions based on reported survey income data and tax-benefit microsimulation. First, we provide a detailed comparison of the number of benefit recipients and taxpayers, as well as aggregate yearly amounts of taxes and benefits obtained under both approaches against external official statistics. Then, we analyse the relative importance of different tax-benefit components across the income distribution in Ecuador. Third, we compare poverty and inequality indicators obtained with ENIGHUR and ECUAMOD data. Finally, we provide a picture of the effect of different tax-benefit components on income poverty and inequality with both approaches and discuss factors driving discrepancies.

3.1 Validation of reported and simulated tax-benefit instruments

Validation of simulated taxes and benefit is a crucial part of microsimulation modelling. In this section, we propose comparing information about the number of benefit recipients and taxpayers as well as aggregate annual expenditure in social benefits and revenue from taxes and SICs obtained with ECUAMOD and reported in ENIGHUR against external official data.

The numbers of recipients of benefits and payers of taxes and SICs obtained with ECUAMOD and reported in ENIGHUR are compared with external benchmarks in Table 1. In terms of benefits, the results show that ENIGHUR data captures around 91 per cent of beneficiaries of the Human Development Transfer compared to external statistics. The underrepresentation in the data is likely to be related to the fact that external statistics report the total number of beneficiaries over the whole year, whereas the survey asks respondents whether they have received the transfer over the past three months. ECUAMOD underestimates the number of recipients of the Human Development Transfer by around 17 per cent compared to external statistics. As mentioned in the previous section, in order to assess eligibility for the HDT in our simulations, we replicated the index of the Social Register with the input data and fixed the threshold of eligibility by identifying the same number of people below the official threshold. Note that this is different from calibrating the number of recipients of the transfer because other eligibility conditions, simulated in ECUAMOD, apply in addition to being below the threshold of the composite index, such as the presence of children in the household or non-affiliation to social security in the case of elderly adults and disabled persons. The underestimation of recipients of the HDT in ECUAMOD could therefore be related to non-fulfilment of eligibility conditions of individuals below the threshold due to differences in characteristics with actual recipients but also to a certain degree of digression from the authorities as to who is considered eligible for the transfer, which cannot be captured in our simulations.

The number of recipients of the disability carer benefit Joaquín Gallegos Lara obtained from ECUAMOD matches those of ENIGHUR because, as previously mentioned, simulations of the disability carer benefit are based on actual benefit receipt in the data. Disability carer benefit cannot be fully simulated because eligibility depends on the severity of disability and this information is unavailable in the data. ENIGHUR and ECUAMOD results underestimate the number of recipients of the disability carer benefit reflecting that this population subgroup is not properly captured by the survey.

In terms of taxes and SICs, ECUAMOD underestimates the number of payers compared with data from the Ecuadorean Social Security Institute (IESS) and the Internal Revenues Service (SRI), which might be related to income underreporting in the underlying input data. Note, however, that the underestimation of personal income tax and SICs payers is even more severe when reported payers from ENIGHUR are compared with external statistics. In particular, ENIGHUR data captures only 43 per cent of personal income taxpayers compared to 70 per cent obtained with ECUAMOD, reflecting the difficulties of collecting tax data in household surveys and highlighting the usefulness of microsimulation to calculate this type of income. The underestimation of self-employed SICs payers in ENIGHUR is related to the fact that the data does not contain information on payments to rural workers’ SICs (Seguro Campesino), which are simulated in ECUAMOD and are included in the official figures. The gap between the number of income taxpayers obtained from ECUAMOD and that of official statistics is most likely driven by income underreporting and underrepresentation of individuals at the top of the market income distribution in ENIGHUR data. Note that in Ecuador (like in many other Latin American countries) deductions from personal expenditures apply to income tax and the exemption threshold for income tax payment is rather high. In 2011, annual incomes below the USD 9,210 threshold were exempt from income tax, whereas the annualised minimum wage was equal to USD 3,168. Most individuals non-affiliated with social security have low earnings and, therefore, even under the assumption of full-compliance in our simulations they would pay no income tax.

Tax–benefit instruments in 2011: number of recipients/payers (in thousands).

| ECUAMOD | ENIGHUR | External | Ratios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (A)/(B) | (A)/(C) | (B)/(C) | |

| Social Benefits | ||||||

| Human Development Transfer | 1,538 | 1,681 | 1,854 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.91 |

| Joaquín Gallegos Lara | 9 | 9 | 14 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Taxes and Social Insurance Contributions (SICs) | ||||||

| Personal income tax | 334 | 204 | 476 | 1.64 | 0.70 | 0.43 |

| Employee SICs | 2,134 | 1,836 | 2,449 | 1.16 | 0.87 | 0.75 |

| Self-employed SICs | 255 | 74 | 341 | 3.46 | 0.75 | 0.22 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations, ENIGHUR 2011–2012 and IESS (2015).

Table 2 presents a validation of reported and simulated aggregate annual expenditure in social benefits and revenue from taxes and SICs. Aggregate expenditure in the HDT from ENIGHUR data matches well the external benchmark, which reflects the fact that survey data in Ecuador captures well the bottom of the income distribution. ECUAMOD simulations underestimate aggregate expenditure in the HDT by around six per cent in comparison to ENIGHUR data and nine per cent with respect to external statistics, which is in line with the underestimation of benefit recipients. Reported and simulated amounts of Joaquín Gallegos Lara transfer underestimate the aggregate amounts compared with external sources by around 40 per cent, reflecting the underestimation of benefit recipients in the data (see Table 1).

In terms of taxes and SICs, our simulations underestimate the aggregate amount of personal income tax and SICs compared with external statistics. ECUAMOD simulations capture around 82 per cent of revenue from personal income tax and 98 per cent of employee SICs. On the other hand, results obtained directly from ENIGHUR data provide an extremely poor match against the external benchmark. Reported personal income tax amounts from ENIGHUR capture only 22 per cent of personal income tax revenue. Reported employee SICs’ amounts provide a better fit, capturing 88 per cent of employee SICs revenue, compared to 98 per cent captured by ECUAMOD results. The poor representation of aggregate annual revenue from personal income tax provided by ENIGHUR data is most likely related to the abovementioned difficulties of reporting this type of deductions in surveys and points to the importance of using simulated taxes to assess the effect of this component on the income distribution, as its effect would be otherwise underestimated. The underestimation of income tax might also be related to the fact that, in general, surveys fail to properly capture the top of the income distribution and this is particularly the case for developing countries like Ecuador. The comparison of simulated and reported revenue from self-employed SICs with respect to official statistics is rather puzzling. Both simulated and reported results overestimate the revenue from self-employed SICs compared to the external benchmark. The results are counterintuitive given that the number of payers of self-employed SICs obtained from ECUAMOD and ENIGHUR underestimates the number of payers with respect to official statistics. The discrepancies might be related to the categories of workers for which SICs revenue has been reported by the authorities. ECUAMOD and ENIGHUR results consider as self-employed any person reporting income from self-employment, whereas external statistics might be based on people officially registered as self-employed at IESS. Finally, Table 2 provides a comparison of aggregate revenue from VAT. Compared with external statistics, ECUAMOD underestimates VAT by around 44 per cent. VAT reported by ENIGHUR represents only 19 per cent of the official aggregate amounts. However, it is worth noting that ENIGHUR reports VAT payments by the self-employed only, as part of their expenditures. VAT payment by households is not directly reported by ENIGHUR. On the other hand, ECUAMOD simulates VAT payments by households only, whereas the official statistics on VAT include payments by both households and firms.

Tax–benefit instruments in 2011: annual amounts (in millions).

| ECUAMOD | ENIGHUR | External | Ratios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (A)/(B) | (A)/(C) | (B)/(C) | |

| Social Benefits | ||||||

| Human Development Transfer | 661 | 706 | 724 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.97 |

| Joaquín Gallegos Lara | 26 | 24 | 41 | 1.07 | 0.62 | 0.58 |

| Taxes and Social Insurance Contributions (SICs) | ||||||

| Personal income tax | 639 | 171 | 784 | 3.75 | 0.82 | 0.22 |

| Employee SICs | 1,478 | 1,322 | 1,508 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 0.88 |

| Self-employed SICs | 332 | 268 | 176 | 1.24 | 1.88 | 1.52 |

| VAT | 1,708 | 592 | 3,073 | 2.88 | 0.56 | 0.19 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations, ENIGHUR 2011–2012 and IESS (2018).

3.2 Relative size of tax-benefit instruments

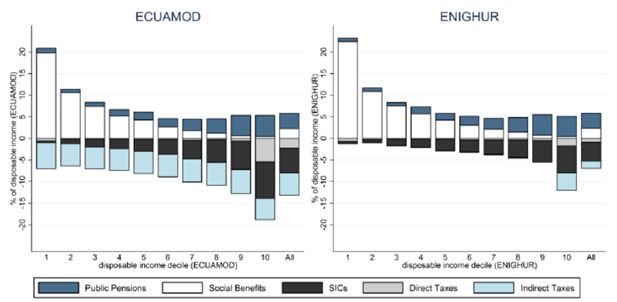

Before comparing poverty, inequality and the redistributive effect of tax-benefit systems between our two approaches, it is worth considering the extent to which the size of different tax-benefit components varies across the income distribution depending on the use of simulated or reported incomes. Figure 1 shows the relative size of five tax-benefit components in Ecuador, where the average size of each income component is measured as a percentage of average household disposable income by household disposable income decile, and on average for the whole population. Direct and indirect taxes, and social insurance contributions are shown as negative values as they are subtracted in the calculation of disposable income.

Under both approaches, our results show that social benefits play an important role at the bottom of the income distribution. Social benefits represent on average 20 per cent of household disposable income for individuals in the bottom decile of the income distribution with ECUAMOD and 22 per cent with reported benefits from ENIGHUR. The slightly larger size of social benefits with ENIGHUR data reflects the fact that ECUAMOD simulations of the Human Development Transfer slightly underestimate the number of recipients and aggregate amounts of this benefit compared to ENIGHUR, as shown in Tables 1 and 2 above.12

ECUAMOD and ENIGHUR results differ more in terms of the relative size of taxes and SICs. Simulated direct taxes represent an important proportion (5.4 per cent) of household disposable income only for the top decile of the income distribution. This might be due to the high exemption threshold for income tax payment and also to the presence of deductions from personal expenditures, which are applied to taxable income. Direct taxes reported in the data account only for 1.7 per cent of household disposable income for the top decile. The discrepancies between ECUAMOD and ENIGUR results might be driven by underreporting or misreporting of personal income tax in ENIGHUR and reflect the difficulties of recording this type of income in surveys. Indirect taxes in ECUAMOD are mostly proportional with respect to disposable income, although the relative size of this income component is slightly larger for the first income decile pointing to a minor regressivity. The mostly proportional nature of indirect taxes is in line with a recent paper by Rojas Baez (2017) and is driven by the presence of a zero per cent VAT rate on goods and services considered basic necessities. The relative size of indirect taxes in ENIGHUR is on average smaller than that of ECUAMOD and they appear to affect mostly the top income decile. Differences between ENIGHUR and ECUAMOD results in terms of indirect taxes are due to the fact that ENIGHUR reports VAT payments from expenditures related to self-employment activities only, whereas VAT payments for all households are calculated in ECUAMOD simulations based on expenditure information available in the survey. Finally, reported and simulated social insurance contributions are progressive in nature but represent a smaller share of household disposable income with results based on ENIGHUR data.

Table 3 confirms the pattern of tax-benefit components with respect to disposable income in our two approaches, where the progressivity of different policy instruments is assessed using the Suits index. The Suits index measures the ratio between the cumulative proportion of a policy instrument (e.g. income tax) and the cumulative proportion of income. The value of the Suits index lies within the interval [−1, 1]. A value of −1 would imply an extremely regressive policy instrument (e.g. the poorest person pays all the tax), whereas a value of 1 depicts extreme progressivity (e.g. the richest person pays all the tax). Our results show that direct taxes and SICs are progressive with respect to disposable income but to a larger extent with results obtained from ECUAMOD. Public pensions are regressive, whereas social benefits are progressive. Finally, ECUAMOD and ENIGHUR provide contrasting results in terms of progressivity of indirect taxes. Reported VAT in ENIGHUR are progressive with respect to disposable income, whereas ECUAMOD results point to a minor regressivity of indirect taxes, which is in line with the fairly proportional nature of this income component (see Figure 1).

Progressivity of tax-benefit components in 2011– Suits index.

| Public Pensions | Social Benefits | Direct Taxes | Social Insurance Contributions | Indirect Taxes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECUAMOD | −0.21 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.25 | −0.03 |

| ENIGHUR | −0.19 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.83 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations and ENIGHUR 2011–2012.

3.3 Poverty and inequality

Table 4 presents the results of our comparison of inequality and poverty indicators calculated from the reported ENIGHUR data and the simulated ECUAMOD data. The results are computed for individuals according to their household disposable income (HDI) per capita (i.e. HDI divided by household size). HDI is calculated as the sum of all income sources of all household members net of income tax and SICs. Using HDI per capita is the approach proposed by the National Institute for Statistics and Census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, INEC) to calculate income poverty and inequality.

In terms of income inequality, Table 4 shows that the Gini coefficient obtained with the two sets of results are very similar. The Gini coefficient obtained from ENIGHUR data is slightly higher (by only three per cent) but the difference with the estimate from ECUAMOD data is small. The same applies to results for the p90/p10 ratio. Table 4 also presents the Atkinson index using three values for the parameter of ‘inequality aversion’, ε = 0.5, 1 and 2. Calculating the Atkinson index for different values of ε allows us to change the importance attached to variations at different points in the income distribution, with larger values of ε being more sensitive to variations at the lower end of the income distribution. ENIGHUR data provides slightly larger estimates for the Atkinson index. The gap between ENIGHUR and ECUAMOD data estimates is the largest for the Atkinson index with ε = 0.5, with a difference of eight per cent of the size of the ECUAMOD estimate.

The second and third sections of Table 4 compare statistics on absolute poverty and extreme poverty headcounts calculated under the two approaches. The national poverty lines of USD 72.87 per month for poverty and USD 41.06 per month for extreme poverty are used in the calculations.13 As it was the case for inequality, absolute poverty and extreme poverty calculated using reported ENIGHUR data are slightly higher than those based on simulated incomes. Our results further distinguish poverty estimates between households living in the urban or rural area of the country. The discrepancies between poverty estimates calculated from ENIGHUR data and ECUAMOD data are more marked in the urban area. The gap between urban extreme poverty from ENIGHUR data and ECUAMOD simulations is around 15 per cent, although this represents 0.4 percentage points given the low levels of extreme poverty in urban areas of the country.

Absolute poverty rates and income inequality in 2011.

| ECUAMOD (A) | ENIGHUR (B) | Ratio (A)/(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inequality | |||

| Gini | 46.1 | 47.7 | 0.97 |

| p90/p10 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 0.96 |

| Atkinson index (0.5) | 17.8 | 19.3 | 0.92 |

| Atkinson index (1) | 30.8 | 32.6 | 0.94 |

| Atkinson index (2) | 50.5 | 52.4 | 0.96 |

| Poverty headcount | |||

| Total | 20.8 | 21.7 | 0.96 |

| Urban | 12.5 | 13.3 | 0.94 |

| Rural | 37.6 | 38.5 | 0.98 |

| Extreme poverty headcount | |||

| Total | 5.7 | 6.2 | 0.94 |

| Urban | 2.3 | 2.7 | 0.85 |

| Rural | 12.7 | 13.3 | 0.95 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations and ENIGHUR 2011–2012.

-

Notes: Computed for individuals according to their household disposable income per capita. Household disposable income is calculated as the sum of all income sources of all household members net of income tax and SICs.

The comparison of poverty and inequality calculated under our two approaches points to only minor differences. However, as observed in the previous section, the relative size and progressivity of particular tax-benefit components can vary considerably depending on the use of reported or simulated incomes. For instance, reported information on personal income tax payments seems to suffer from underreporting in the survey, which translates into a modest impact of reported income tax on household disposable income (see Figure 1). ECUAMOD simulations match better external statistics and translate into a larger effect of income tax at the top of the income distribution and therefore lower income inequality. From a policy perspective, it is important to have a clear idea of the effect of individual tax-benefit instruments on poverty and inequality. This is particularly relevant given the different degrees of measurement errors (e.g. underreporting or underrepresentation of top incomes) that individual income components might suffer from. The following section compares the extent to which the effect of tax-benefit components differs depending on whether reported or simulated incomes are used in the analysis.

3.4 The effect of taxes and benefits on income inequality and poverty

Assessing the role of taxes and benefits in reducing poverty and inequality is essential to improve the design of existing and new policy instruments. Table 5 compares results for the Gini coefficient, the poverty headcount and extreme poverty headcount of household disposable income and household market income per capita under our two approaches. The results show that direct taxes and cash transfers reduce income inequality by 4.1 points (50.2 minus 46.1) based on ECUAMOD data. The redistributive effect of the tax-benefit system is reduced by almost half based on ENIGHUR data, accounting for 2.5 points reduction in inequality (50.2 minus 47.7). Absolute poverty is reduced by 4.1 points when simulated disposable income is compared to market income, whereas a 3.2 points decrease is observed with reported incomes from ENIGHUR data. The effect of the tax-benefit system on extreme poverty is more similar between the two approaches: extreme poverty is reduced by 3.7 (3.2) points when ECUAMOD (ENIGHUR) data is used.

Effect of the tax-benefit system on income inequality and poverty in 2011.

| Market income | Disposable income (DPI) | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gini coefficient | |||

| ECUAMOD | 50.2 | 46.1 | 4.1 |

| ENIGHUR | 50.2 | 47.7 | 2.5 |

| Poverty headcount | |||

| ECUAMOD | 24.9 | 20.8 | 4.1 |

| ENIGHUR | 24.9 | 21.7 | 3.2 |

| Extreme poverty headcount | |||

| ECUAMOD | 9.4 | 5.7 | 3.7 |

| ENIGHUR | 9.4 | 6.2 | 3.2 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations and ENIGHUR 2011–2012.

The effect of specific tax-benefit components on income inequality and poverty under our two approaches is presented in Tables 6 and 7. The marginal contribution of individual tax-benefit components is obtained from the difference between inequality/poverty for disposable income with and without the tax-benefit component in question. As such, in order to assess the effect of public pensions and social benefits, we subtract each component separately from disposable income and recalculate income inequality and poverty. In order to assess the effect of direct taxes and SICs, we add back each component separately to disposable income and recalculate poverty and inequality. Finally, we also present poverty and inequality estimates for disposable income minus indirect taxes.

Under both approaches, the income component that reduces inequality the most is social benefits; accounting for a reduction of around 1.7 points, when Gini for disposable income is compared to Gini for disposable income minus social benefits (column A minus column C). The role of public pensions is minor in both cases. Table 6 points to a very different effect of direct taxes and SICs depending on the approach used in the analysis. SICs reduce income inequality by 1.3 points based on ECUAMOD data, whereas the effect of SICs is 0.9 points when reported incomes are used (column A minus column E). The differences are even more striking for direct taxes, which contribute to inequality reduction by 1 point with ECUAMOD data and only 0.3 points with ENIGHUR data (column A minus column D). Finally, indirect taxes tend to slightly increase inequality according to ECUAMOD simulations, whereas inequality decreases by 0.8 points when the Gini for disposable income is compared to the Gini for disposable income minus indirect taxes reported in ENIGHUR (column A minus column F).

Effect of tax-benefit components on income inequality in 2011.

| Disposable income (DPI) | DPI minus Public Pensions | DPI minus Social Benefits | DPI plus Direct Taxes | DPI plus SICs | DPI minus Indirect Taxes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | |

| ECUAMOD | 46.1 | 46.3 | 47.8 | 47.1 | 47.4 | 46.2 |

| ENIGHUR | 47.7 | 47.9 | 49.4 | 48.0 | 48.6 | 46.9 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations and ENIGHUR 2011–2012.

Table 7 presents the effect of tax-benefit instruments on absolute poverty and extreme poverty under our two approaches. The income component that reduces poverty and extreme poverty the most is social benefits and the effect is very similar under the two approaches. Social benefits reduce poverty by 3.4 points and extreme poverty by 2.9 points with both ECUAMOD and ENIGHUR data (column A minus column C). The effect of public pensions is also similar under the two approaches, reducing poverty by around 1.4 points and extreme poverty by around 1 point (column A minus column B). The role played by direct taxes and SICs is, on the other hand, very modest under the two approaches and adding them back to disposable income results in slightly lower poverty levels. Finally, our two approaches provide a very different picture of the effect of indirect taxes. Subtracting indirect taxes from disposable income increases poverty by 2.1 points and extreme poverty by 0.9 points based on simulated data from ECUAMOD, whereas neither poverty nor extreme poverty are affected when reported VAT is deducted from disposable income calculated from ENIGHUR data (column A minus column F).

The results presented in this section highlight the extent to which individual tax-benefit instruments might be subject to different degrees of measurement error depending on the approach used for the analysis, and the effect of such differences on income inequality and poverty. On the one hand, the effect of social benefits on income inequality and poverty is similar under the two approaches. However, it is important to bear in mind that ECUAMOD results underestimate the number of HDT beneficiaries due to the complexity of simulating eligibility rules for this cash transfer. On the other hand, the larger effect of simulated direct taxes on income inequality reflects the fact that reported tax payments in the data suffer from underreporting or misreporting and therefore simulating personal income tax based on market income information available in the survey captures a larger number of taxpayers. As noted before, problems of underreporting and underrepresentation of the top of the market income distribution also result in an underestimation of tax revenue if ECUAMOD results are compared to external statistics. Finally, the use of comparable income information under both approaches has an important effect on the results. Our two approaches provide a very different picture of the effect of indirect taxes. This is due to the fact that indirect taxes reported in ENIGHUR relate only to VAT payments from expenditures linked to self-employment activities, whereas ECUAMOD results represent VAT payments by all households calculated from expenditure information available in the survey.

Effect of tax-benefit components on income poverty in 2011.

| Disposable income (DPI) | DPI minus Public Pensions | DPI minus Social Benefits | DPI plus Direct Taxes | DPI plus SICs | DPI minus Indirect Taxes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | |

| Poverty headcount | ||||||

| ECUAMOD | 20.8 | 22.3 | 24.2 | 20.7 | 20.3 | 22.9 |

| ENIGHUR | 21.7 | 23.1 | 25.1 | 21.6 | 21.4 | 21.7 |

| Extreme poverty headcount | ||||||

| ECUAMOD | 5.7 | 6.7 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.6 |

| ENIGHUR | 6.2 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

-

Source: ECUAMOD version 1.4 calculations and ENIGHUR 2011–2012.

4. Conclusions

The analysis of the redistributive effect of tax-benefit systems in developing countries is paramount for the improvement of existing policies and the development of new instruments with the view of strengthening social protection. In this paper, we compared the redistributive effect of taxes and benefits in Ecuador under two different approaches. The first approach involved using reported information on taxes and benefits from ENIGHUR data, whereas the second approach made use of the newly developed microsimulation model for Ecuador, ECUAMOD, to calculate tax-benefit instruments.

Under the two approaches compared in this study, data quality plays an important role. Our results show that ENIGHUR data provides a poor representation of the number of taxpayers and aggregate tax revenue relative to tax records, which is most likely related to underreporting or misreporting. ECUAMOD simulations of personal income tax match better external statistics, but still capture only 82 per cent of tax revenue. Income underreporting and underrepresentation of rich individuals in household survey data are the likely drivers of this discrepancy as market income information is taken directly from ENIGHUR data for the simulation of income tax. In terms of benefits, ENIGHUR data captures very well the number of recipients and aggregate amounts of the Human Development Transfer, the main social assistance benefit in Ecuador. ECUAMOD simulations, on the other hand, underestimate the number of HDT beneficiaries and aggregate expenditure. This reflects the difficulties of simulating complex eligibility rules in microsimulation models, in our case, reproducing the composite index of eligibility for the Human Development Transfer.

Our results further show the extent to which inequality and poverty indicators vary due to differences between reported and simulated taxes and benefits. Inequality and poverty indicators obtained from ECUAMOD simulations slightly underestimate those based on ENIGHUR data. The Gini coefficient for disposable income is 1.6 points lower with ECUAMOD data compared to ENIGHUR data (46.1 compared to 47.7), whereas the absolute poverty headcount is 0.9 points lower (20.8 compared to 21.7). Under both approaches, social assistance benefits are the instrument that has the largest effect in inequality reduction and the size of its effect is similar with ENIGHUR and ECUAMOD data. However, important differences between the two approaches are observed in terms of the redistributive effect of direct taxes. Based on ENIGHUR data, direct taxes reduce inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, only by 0.3 points, whereas the effect is of 1 point based on ECUAMOD simulations. The discrepancies between the two approaches reflect the fact that personal income tax is poorly captured in the household survey data. As such, our results point to a much larger effect of direct taxes in reducing inequality compared to previous studies, which have either used reported incomes or imputed taxes from other sources into survey data.

The findings presented in this paper have focused on the extent to which income inequality and poverty estimates obtained from the newly developed tax-benefit model ECUAMOD are consistent with those obtained directly from ENIGHUR data. An alternative direction for the study of the redistributive effect of actual tax-benefit systems could have made use only of those simulated components which match better external statistics; in our case, social insurance contributions and personal income tax. The redistributive effects of the tax-benefit system in Ecuador under such exercise are similar to those of ECUAMOD, as it is mainly the redistributive effect of income taxes that differs between the two approaches. It should be noted, however, that the study of the redistributive effect of actual or current tax-benefit policies is only one of many applications of microsimulation models. In principle, simulating as many instruments as possible is more desirable for exercises in which reforms to such policies would be simulated.

The results presented here suggest a number of extensions and directions for future research based on ECUAMOD. First, the underestimation of the number of taxpayers and aggregate tax revenue from ECUAMOD simulations, due to problems underreporting and underrepresentation of the top of the market income distribution in household surveys, points to the need of enriching survey data. Imputations based on administrative tax records could be considered in future versions of the model to assess their impact on the simulations. Second, the possibility of relaxing the assumption of full compliance with tax rules should be considered through the simulation of some sort of tax-evasion based on information collected by the public administration or on different definitions of informality. Third, we should consider extending the scope of our simulations to provide a broader picture of the role of the welfare state, for instance, through simulating indirect fuel subsidies. Finally, the development of a regional tax-benefit microsimulation model for Latin America, using a common harmonised language, represents an important opportunity for policy developments and collaborations within the region. Progress on this area is already being made with the development of a microsimulation model for Colombia, which allows performing comparative analysis (Bargain, Jara, & Rodriguez, 2017). All these issues represent promising areas for future research.

Footnotes

1.

Differences between INEC (2016) figures and the results presented in this study are due to the use of different surveys in the analysis. INEC (2016) figures are based on the National Survey of Employment, Underemployment and Unemployment (Encuesta Nacional de Empleo, Desempleo y Subempleo, ENEMDUR).

2.

For more information about CEQ, see http://www.commitmentoequity.org/.

3.

The nine self-represented cities are: Cuenca, Machala, Esmeraldas, Guayaquil, Loja, Manta, Quito, Ambato, and Santo Domingo.

4.

Respondents are asked to report how much was deducted from their monthly gross income in terms of social insurance contributions. Additionally, the survey asks employees to report how much was deducted from their monthly gross income in terms of income tax, and the self-employed to report how much income tax they paid over the last twelve months.

5.

Market income is the sum of employment and self-employment income, bonuses, in-kind income, self-consumption from self-employment activities, capital and property income, inter-household payments, private transfers, minus alimony payments. Imputed rent is not included as part of market income.

6.

Utilities participation is a benefit for employees, where 15 per cent of a firm’s utilities are distributed among all employees in the firm.

7.

Deductions from personal expenditures cannot be higher than 50 per cent of taxable income or 1.3 times the basic exempted band. Additionally, there are individual limits for each type of expenditure. Expenditure in food, housing, education, and clothing cannot exceed 0.325 times the basic exempted band, individually. Expenditure in health cannot exceed 1.3 times the basic exempted band.

8.

In 2016, the VAT rate was increased to 14 per cent in all provinces except those hit by the earthquake in April 2016.

9.

For more details about the simulation of ICE in ECUAMOD see Jara et al. (2017).

10.

Additionally, the conditionality of the programme extends to prenatal health controls, sexual and reproductive health consultations, eradication of child labour and mendacity, maintenance of the dwelling, and an annual update of changes in the socio-economic situation of the household.

11.

Our pseudo index might be upward biased with respect to the official index, as the sample used to calculate the official index targets, a population in potential need of social protection.

12.

Previous studies based on the National Survey of Employment, Underemployment and Unemployment (ENEMDUR) have focused on the percentage of HDT beneficiaries along the income distribution or concentration shares, rather than the relative size of the HDT by deciles. Burgos Dávila (2014) shows that around 26 per cent of HDT beneficiaries are in the two lowest income quintiles, whereas ECUAMOD finds 36 per cent of beneficiaries in the two lowest income quintiles and ENIGHUR 35 per cent. In terms of concentration shares, around 38.7 per cent of the total budget allocated to the BDH is concentrated among the two lowest income quintiles according to Ponce (2011), whereas results based on ECUAMOD amount to 36.3 per cent and those based on ENIGHUR data directly to 35.05 per cent.

13.

The extreme poverty line in Ecuador is defined in terms of the minimum value of a food consumption basket to satisfy the nutritional needs for a healthy life. The poverty line is then obtained by using the inverse of the Engel coefficient (which measures the relationship between expenditure in food consumption and expenditure in total consumption) to scale the extreme poverty line (INEC 2015).

Appendix

Simulation of taxes and benefits in ECUAMOD.

| Policy instrument | Treatment in ECUAMOD | Why not fully simulated? |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated tax-benefit instruments | ||

| Employee social insurance contributions | Simulated | - |

| Armed forces and police | ||

| social insurance | Simulated | - |

| contributions | ||

| Self-employed social insurance contributions | Simulated | - |

| Employer social insurance contributions | Simulated | - |

| Government social | ||

| insurance contributions for | Simulated | - |

| armed forces and police | ||

| Personal income tax | Simulated | - |

| Human development transfer (HDT) | Simulated | - |

| Joaquín Gallegos Lara | Partially simulated | Eligibility for the benefit cannot be simulated to lack of information about severity of disability in the data |

| Value added tax (VAT) | Simulated | - |

| Special consumption tax (excise duties) | Simulated | - |

| Non-simulated tax-benefit instruments | ||

| Old-age pension | Included | No data on contribution records |

| Invalidity pension | Included | No data on contribution records |

| Survivors’ pension | Included | No data on contribution records |

| Injury benefit | Included | No data on contribution records |

| Severance payments | Included | No data on contribution records No information about students’ |

| Scholarships | Included | grades to determine eligibility for scholarships |

| Housing grant | Included | No information about the price of the property individuals intend to buy nor about the cost of planned remodelling for their current house |

| Property tax and property transfer tax | Included | No information on property values in the data |

| Wealth tax | Included | No information on wealth in the data |

| Motor vehicle tax | Included | No information on vehicle values in the data |

-

Source: Authors’ compilation.

References

-

1

Learning from your neighbour: Tax-benefit systems swaps in Latin AmericaJournal of Economic Inequality 15:369–392.

-

2

Tax compliance: when do employees behave like the self-employed?Applied Economics 37:1201–1208.

-

3

Pobreza por ingresos y eliminación de transferencias monetarias condicionadas: el caso del bono de desarrollo humano en Ecuador (Nota técnica no. 7)Económica – CIC.

-

4

Towards a more realistic Estimate of the Income Distribution in MexicoLatin American Policy 8:114–126.

-

5

Top Income Shares in a Growing South American Economy: Ecuador 2004–2011 (University Toulouse 1 Capitole. Working PaperToulouse: University of Toulouse.

-

6

(Estudio no. 8). Serie “Estados de la Cuestión”Los efectos de la política fiscal sobre la redistribución en América Latina y la Unión Europea, (Estudio no. 8). Serie “Estados de la Cuestión”, http://sia.eurosocial-ii.eu/files/docs/1412088027-Estudio_8_def_final.pdf.

-

7

Are household surveys like tax forms: evidence from income underreporting of the self-employedReview of Economics & Statistics 96:19–33.

- 8

-

9

Recaudación Anual por aportes al Seguro General ObligatorioRecaudación Anual por aportes al Seguro General Obligatorio, Oficio Nro. IESS-DG-2018-0223-OF, Quito, IESS.

-

10

Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los hogares urbanos y rurales 2011- 2012Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los hogares urbanos y rurales 2011- 2012, Resumen Metodológico y Principales Resultados, Quito, INEC.

-

11

Metodología de construcción del agregado del consumo y estimación de línea de pobreza en el EcuadorINEC.

-

12

Retrieved fromReporte de Pobreza y Desigualdad, December, Retrieved from, http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/POBREZA/2016/Diciembre_2016/Reporte%20pobreza%20y%20desigualdad-dic16.pdf.

-

13

Approximations to the truth: comparing survey and microsimulation approaches to measuring income for social indicatorsSocial Indicators Research 105:387–407.

-

14

Microsimulation and Policy AnalysisIn: AB Atkinson, F Bourguignon, editors. Handbook of Income Distribution, 2B. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 2141–2221.

-

15

Desigualdad, concentración del ingreso y tributación sobre las altas rentas en América LatinaLa tributación sobre las altas rentas en América Latina, Desigualdad, concentración del ingreso y tributación sobre las altas rentas en América Latina, Libros de la CEPAL, No. 134 (LC/G. 2638-P) Santiago de Chile, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

- 16

-

17

Social Spending, Taxes and Income Redistribution in EcuadorSocial Spending, Taxes and Income Redistribution in Ecuador, Documento de trabajo del CEQ núm 28, Instituto CEQ, Tulane University/ FIDA / ICEFI, Washigton D. C. /Roma /Guatemala.

-

18

El impacto del sistema tributario y el gasto social en la distribución del ingreso y la pobreza en América Latina. Una aplicación del marco metodológico del Proyecto Compromiso con la Equidad (CEQ)El Trimestre Económico LXXXIV:335–568.

-

19

The impact of questioning method on measurement error in panel survey measures of benefit receipt: evidence from a validation studyJournal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 175:289–308.

-

20

The under-reporting of transfers in household surveys: its nature and consequences (NBER Working Paper 1518)Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

21

An expenditure-based estimate of Britain’s black economyJournal of Public Economics 39:17–32.

-

22

Working PaperDesigualdad del ingreso en Ecuador: un análisis de los años 1990s y 2000s. FLACSO, Working Paper, May, Retrieved from, http://www.flacsoandes.edu.ec/web/imagesFTP/1309287045.DTFLACSO_2011_Ponce.pdf.

-

23

Decreto Ejecutivo No. 1838Decreto Ejecutivo No. 1838, Official Registry No. 650, 6, August, Ecuador, Government of Ecuador.

-

24

Decreto Ejecutivo No. 422Decreto Ejecutivo No. 422, Official Registry No. 272, 6, August, Ecuador, Government of Ecuador.

-

25

Decreto Ejecutivo No. 1395Decreto Ejecutivo No. 1395, Official Registry No. 870, 14, January, Ecuador, Government of Ecuador.

-

26

Microsimulador de imposición indirecta del departamentp de estudios tributarios (MIIDET)Centro de Estudios Fiscales, Servicio de Rentas Internas.

-

27

Impuesto a la Renta de Personas Naturales en Relación de Dependencia. Un Análisis de Equidad y RedistribuciónImpuesto a la Renta de Personas Naturales en Relación de Dependencia. Un Análisis de Equidad y Redistribución, Documento de Trabajo No. 2010-01, Centro de Estudios Fiscales, Servicio de Rentas Internas.

-

28

Un diseño socialmente eficiente del impuesto a la renta de personas naturales. Aplicaciones técnicas de microsimulación en EcuadorUn diseño socialmente eficiente del impuesto a la renta de personas naturales. Aplicaciones técnicas de microsimulación en Ecuador, Documento de Trabajo No. 2010-09, Centro de Estudios Fiscales, Servicio de Rentas Internas.

-

29

Microsimulador del Impuesto a la Renta de Personas Jurídicas MIR(PJ)Microsimulador del Impuesto a la Renta de Personas Jurídicas MIR(PJ), Año, Centro de Estudios Fiscales, Servicio de Rentas Internas.

-

30

Análisis de regresividad del IVA en el EcuadorAnálisis de regresividad del IVA en el Ecuador, Notas de Reflexión, Política fiscal y tributaria, 40, Quito, Centro de Estudios Fiscales, Servicio de Rentas Internas.

-

31

EUROMOD: the European Union Tax-benefit Microsimulation ModelInternational Journal of Microsimulation 6:4–26.

Article and author information

Author details

Acknowledgements

The results presented here are based on ECUAMOD v1.4. ECUAMOD is developed, maintained and managed by UNU-WIDER in collaboration with the EUROMOD team at ISER (University of Essex), SASPRI (Southern African Social Policy Research Institute) and local partners in selected developing countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, Ecuador and Vietnam) in the scope of the SOUTHMOD project. The local partner for ECUAMOD is Instituto de Altos Estudios Nacionales (IAEN). We are indebted to the many people who have contributed to the development of SOUTHMOD and ECUAMOD. We would also like to thank two anonymous referees for valuable comments on previous versions of the paper. The results and their interpretation presented in this publication are solely the authors’ responsibility.

Publication history

- Version of Record published: April 30, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Jara and Varela

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.