Quality assessment of microsimulation models. The case of EUROMOD

Abstract

Assessing the quality of microsimulation models is an important contributing factor for motivating their use in both academic and policy environments. This is particularly relevant for EUROMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for the European Union, because it is intended to be widely used. This paper explains how the quality of EUROMOD is assessed. It focusses on the validity and scope of results as particularly important dimensions of quality, and on the transparency with which this assessment is done. It also provides evidence on the extent and breadth of the use of EUROMOD. Some of the key trade-offs between different aspects of quality are identified and the paper concludes with a view on the appropriate division of responsibility for quality assessment, between model developers and users.

1. Introduction

Assessing the quality of microsimulation models is an important contributing factor for motivating their use in both academic and policy environments, for providing guidance in the appropriate use of such models and in the interpretation of results obtained from them.

The purpose of microsimulation models is to generate data that do not otherwise exist, usually describing some counterfactual situation which can be compared with the existing state of play. There are many potentially relevant dimensions of “quality” and their importance depends on the particular exercise being carried out. The dimensions that are feasible to assess meaningfully are limited to those for which there are independent benchmarks, standards or expectations against which to compare. There are many varieties of microsimulation models with different purposes and underlying methodologies and technologies (O’Donoghue, 2014). All of this means that it is difficult to discuss quality in abstract or general terms. To provide a concrete focus, this paper refers explicitly to the quality assessment of one particular model, EUROMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for the European Union (EU). It concentrates on one important, generally applicable dimension of quality: the validity and scope of results. EUROMOD has a long-standing tradition of being made openly available to the academic and policy community. The result is a well-developed set of practices and protocols for ensuring high quality. Given this, the paper also presents some evidence giving an indirect outcome indicator of EUROMOD’s quality: the extent and breadth of its use.

The aim of this paper is two-fold. It is, first, a description of how some central aspects of EUROMOD’s quality are assessed in order to best inform users about what they can expect from EUROMOD, and how to interpret results obtained from it. It is a statement of model quality, especially focussed on the validity and scope of results, for users to refer to. The second aim is to establish some benchmark standards against which the future evolution of EUROMOD can be compared. This is particularly relevant as responsibility for EUROMOD’s updating and maintenance transfers from an academic setting at the University of Essex to the European Commission.1 It provides an opportunity to pass on the lessons we have learned not only to those who will take over, but also to the wider microsimulation community.

Before considering the quality of a model and its estimates it is important to provide a statement of the purpose of the model. This is done for EUROMOD in Section 2. Section 3 then describes in some detail how the quality of EUROMOD estimates is assessed and what the main challenges are, both to achieving high quality and to its assessment. No actual assessment is reported since this is very detailed and extensive and cannot be summarised meaningfully and also because it would be quickly out of date as improvements are always being made. Instead, the discussion refers the reader to where they can find the most recent information. Section 4 presents some evidence on the use of EUROMOD and Section 5 concludes by drawing out some general lessons for EUROMOD and for the quality assessment of microsimulation models more generally.

2. What is euromod and what is it for?

EUROMOD is a multi-country tax-benefit microsimulation model for the 28 member states of the EU based on representative household micro-data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). EUROMOD is designed for comparable simulations and analysis across countries as well as for policy swaps and EU level analysis (Sutherland, 2014). For some countries it is the only accessible tax-benefit model and so is also used for single-country analysis.

EUROMOD is extensively used by both the academic and policy communities for the analysis of the effects of tax-benefit policies, and reforms to them, on the household income distribution, public budgets and individual work incentives. Both main inputs —policy rules and input micro-data— are currently updated annually and there is an accumulating time series of policy systems and data combinations.2

2.1 How EUROMOD works

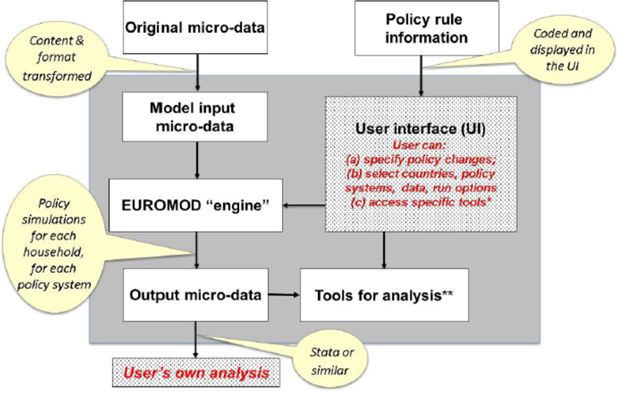

A simplified representation of EUROMOD is shown in Figure 1. The shaded area indicates what happens inside the model and the boxes outside show what feeds in (an original micro-data collection, plus information about policy rules, to be coded in the model) and out (micro-data including simulated output variables for analysis by the user). The dotted boxes show where the user can interact with the model and the call-outs describe the main processes. Within the model, coded tax-benefit policy rules are presented through the model interface. Once the user has made the changes and selected the options and tools that they want to use, the model “engine” calculates household disposable income and its policy components for each household in the input data, for each policy system and country that has been selected by the user. EUROMOD outputs the detail of the simulated policies at micro-level (for each household) to be analysed separately using a statistical software package. It also provides tools within the model to calculate a set of summary statistics (largely pre-defined, with some user-defined options) or to analyse policy effects across the income distribution using a specific methodology.

The structure of EUROMOD.

Notes: *Special tools for calculation of work incentives (METR) and analysis with hypothetical households (HHOT). **Analysis tools are the Statistics Presenter and the Policy Effects tool.

EUROMOD simulates as much as possible of the policy components of household disposable income (direct taxes and employee/self-employed social contributions plus cash benefits) and also employer social insurance contributions and minimum wage rules. Some elements, such as most pension incomes, certain other contributory benefits and disability benefits, cannot be simulated because of lack of relevant variables in the EU-SILC and in this case amounts received are taken from the micro-data instead. For the remainder, EUROMOD simulates benefit entitlements and income tax and social contribution liabilities based on information in the EU-SILC about the person, their income and their household, together with coded policy rules. This is done either for an existing policy system or a reform specified by the user using a purpose-built user interface and tax-benefit calculation language. Results are available at the micro (household) level and can be assembled and compared to show the impact of changes across the income distribution or by other household characteristics, on the public budget, on poverty and inequality and work incentives; or used to inform other types of analysis, such as the estimation of changes to labour supply.

EUROMOD first began development in 1996 and 20th anniversary celebrations were held in 2016.3 For descriptions of successive developments of the same fundamental approach (see Immervoll & O’Donoghue, 2001; Immervoll, O’Donoghue, & Sutherland, 1999; Lietz & Mantovani, 2007; Sutherland, 2001; Sutherland & Figari, 2013). EUROMOD’s longevity is an indicator of its persistent relevance and a testament to its quality. EUROMOD is unique in covering so many countries in a common framework. It is also distinctive in being accessible, flexible and adaptable. These special features are briefly described in turn.

2.2 Accessibility

Many microsimulation models are private to their developers but EUROMOD is openly available and intended to be used in many ways by many users in both academic and policy contexts (Sutherland & Figari, 2013). It is therefore designed to be flexible in many dimensions, with options and assumptions made transparently, and with built-in tools for easy access to key types of analysis.

An updated, tested and openly-validated version of EUROMOD is released to the user community once a year, accompanied by new editions of documentation. A website provides information about how to become a hands-on user, how to access training and support, where to find existing papers and reports using EUROMOD, how to download baseline statistics and to sign up for email alerts, and to receive the regular newsletter EUROMODnews.4

Access to input micro-data is clearly vital but is an area where data providers’ policies vary and can shift over time. In the case of EUROMOD, users must secure their own permission to access the EU-SILC (from Eurostat) or other input data from their respective providers.5 In making choices about which input data to use as standard in EUROMOD, permission to access by the user community (academic and not-for-profit researchers and analysts) is prioritised over other quality considerations.

2.3 Flexibility

EUROMOD is made as flexible as possible not only to make it useful for multiple purposes but also in order to ensure consistency of results and transferability of tax-benefit system components across countries (Sutherland, 2014). The extent of choice available to the user is maximised within a disciplined structure. EUROMOD features that contribute to its flexibility include, firstly, a special-purpose ‘tax-benefit modelling’ language which includes a set of functions that in combination allow the coding of practically any policy. Secondly, the user interface not only provides guided access to this functionality but also a wide range of options that are in the control of the user. Thirdly, there are in place a set of well-developed work practices and protocols that aim to maximise user choice on the one hand while maintaining cross-country comparability and consistency, on the other. One example is the use of a structured naming convention for variables.

2.4 Adaptability

Basic EUROMOD is a static tax-benefit “calculator” for the EU-28 using EU-SILC micro-data. But its design allows it to be adapted in a number of ways. First, it can be used in conjunction with other tools and models: for example, with econometric models of labour supply behaviour (Bargain, Orsini, & Peichl, 2014) or with macroeconomic models of various kinds (for instance Barrios et al., 2017).

Secondly, it is not necessarily limited to the policy scope that is made possible with the EU-SILC and there are examples of projects that make use of the modelling platform to extend the scope of simulations to indirect taxes, making use of Household Budget Survey (HBS) data (De Agostini, Capeau, et al., 2017), to improve the precision of income tax simulations by using administrative tax data or HBS data, for the simulation of tax expenditures; or to extend policy scope to include wealth taxes using the ECB Household Finance and Consumption Survey (Kuypers, Figari, & Verbist, 2018).6

Thirdly, a tool, known as the Hypothetical Household Tool (HHoT), allows the user to generate input data for EUROMOD based on hypothetical (rather than real) households of the user’s own specification (EUROMOD, 2017). This can then be used for “model family” (also known as “synthetic household”) analysis, allowing a focus on household types of particular relevance to the research or policy question, including complex or atypical households (for instance 3+ generations). This moves beyond what is possible with standard estimates of this type, for example from OECD (Gasior & Recchia, 2018). Budget constraints derived from these calculations can also be very useful for checking the validity of the tax-benefit calculations.

Finally, the adaptability of EUROMOD is further demonstrated by its use as a platform for modelling non-EU countries, providing a framework and short-cut to build a coherent and well-functioning model quickly, and also the potential for such a model to be comparable to those of the EU-28 in EUROMOD itself. The pioneer “spin-off” model was SAMOD for South Africa (Wilkinson, 2009; Wright, Noble, Barnes, McLennan, & Mpike, 2016a) and was followed by models for Russia (Popova, 2012), Serbia, (Randelovic & Zarkovic Rakic, 2012), Macedonia (Mojsoska Blazevski, Petreski, & Petreska, 2013), Australia (Hayes & Redmond, 2014), Namibia (Wright, Noble, & Barnes, 2014; Wright, Noble, Barnes, McLennan, & Mpike, 2016b) and then, as part of the SOUTHMOD project, five more African countries (Ghana, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia), and Vietnam and Ecuador (Amores & Jara Tamayo, 2018).7 Such “spin-off’ models can also be constructed for regions and one such example is for Trento, Italy (Azzolini, Bazzoli, De Poli, Fiorio, & Poy, 2014).8

3. Validity and scope of EUROMOD results

Tax-benefit microsimulation models such as EUROMOD depend heavily on micro-data and the quality of the models depends directly on the quality of their input data. Many of the challenges to model quality may be due to deficiencies in the data such as a lack of representativeness of the population or under-reporting for some income sources, or small sample sizes, which should typically be reflected in the Quality Reports for the data themselves.9 It is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a comprehensive assessment of the quality of EUROMOD’s input data. The content of the input micro-data is also a critical determinant of which policies can be simulated accurately (for instance most family benefits), which must rely on imputations and approximations (for instance tax reliefs for the cost of education), and which cannot be simulated at all (for instance variation in local taxes if no within-country location information is provided in the data). The quality and fitness-for-purpose of the input micro-data are important factors, but not the only ones, affecting each of the four aspects of the quality (validity) of estimates from the model that are considered in turn below. These are (i) the validity of baseline estimates,10 (ii) the scope of simulation, (iii) comparability across countries of estimates and (iv) validity of the estimates of the effects of policy (and other) changes. Under each heading the general issues are discussed, followed by a description of EUROMOD practices and specific related data and conceptual issues.

3.1 Validity of baseline estimates

Ideally, the user wants a tax-benefit microsimulation model to generate baseline results that are the same as estimates provided from independent official statistics for an equivalent policy system and time-period. Most relevant are those describing components of the simulation results such as income tax revenue and number of tax-payers, or expenditure on, and number of beneficiaries of, a particular benefit, as there are often administrative statistics available with which they can be compared. Ideally one would want to compare the distributions or breakdowns by type of payer/recipient, as well as making comparisons of aggregates. But in practice one is limited by the available published external information.

A second type of baseline validation comparison involves the use of at-risk-of-poverty and income inequality statistics based on the micro-data source used as input data and conceptually equivalent measures using simulated incomes from the relevant baseline. This is informative in that it abstracts from any problems of representativeness of the micro-data (discrepancies have some other explanation) and provides quality indicators that are relevant and familiar. It is also important for users of results from the model to understand that simulations do not usually exactly reproduce the distributional outcomes found in the data. Figari, Paulus, & Sutherland (2015) discuss the possible causes of discrepancies between income distribution based directly on survey (or other micro-) data and that based on simulated incomes, especially in cross-country comparative perspective. Figari, Iacovou, Skew, & Sutherland (2012) focus particularly on the case of the EU-SILC and EUROMOD.

Market incomes in the data should be assessed against independent evidence where this exists. In many contexts it is desirable that results from the model are consistent with National Accounts. Consistent comparisons and a full reconciliation are complex (Anand & Segal, 2015; Figari et al., 2015) and it should be clear that some strategies to increase validity of baseline results in relation to National Accounts (for instance through re-weighting) and may reduce the validity of estimates of the effects of policy changes.11 For this reason, such adjustments are not routinely carried out in EUROMOD. However, users can make their own calibrations and adjustments either within the model (for instance by adjusting income-component uprating factors or benefit take-up probabilities) or outside it (for instance by re-calculating weights).

3.1.1 EUROMOD practice

The main vehicle for providing users with information that allows them to assess the quality of EUROMOD baseline calculations on a country-specific basis is the Country Report. Each year, to accompany the latest release of EUROMOD, a Country Report is published for each of the 28 countries, each with equivalent content and common structure.12 The reports refer to the use of the latest input data and the simulation of policies applying in each year from the income reference year of the data up to the current year (for example, in December 2017 the reports refer to EU-SILC 2015 and cover policies from 2014 to 2017 inclusive). The first section of the Country Report introduces the policy systems. The second section explains which policies are simulated and how, in some detail, including providing information about all the assumptions made (for instance to account for the non-take-up of benefits in some cases) and the reasons why some components are not simulated. The third section describes the input data and explains any imputations and special features in the production of the EuRoMoD input dataset. The fourth section validates the baseline results according to a standard “macro-validation” procedure (described below) and the final section summarises the main issues and problems that the user should be aware of (“health warnings”). An appendix contains an analysis showing the effects of policy changes in the latest year across the income distribution, with a commentary on the policy changes (or lack of them) that explains the effects shown.

Comparison with external aggregate statistics is a process known as “macro-validation”. The weighted number of recipients/payers for each policy instrument, simulated or not simulated, in the EuRoMoD baseline are compared with figures taken from national administrative statistics for the same period. Similarly, the amounts of annual benefit expenditures and tax revenues are compared between EUROMOD estimates and national administrative figures. In addition, distributional statistics for market incomes, and especially earnings, are compared with those from external statistics, where possible.

Comparisons are often not straightforward to carry out for a number of reasons. First, the administrative statistics on recipients/payers of an instrument may refer to a different unit of analysis than that used by EUROMOD as standard. Making use of EUROMOD’s flexibility these can usually be aligned. Secondly different reference time periods may be used. The EU-SILC has an annual reference period but administrative statistics often count recipients at a point in time. Thirdly, the administrative statistics may not refer to the same distinct instruments or income components that are itemised in EUROMOD. They may refer to sub-instruments or to combinations of several instruments. In some cases, they are only available with a long time delay and in others they are not made publicly available at all. Furthermore, the process of validation is cumulative. If there is a problem with one income component, this will also affect the precision of simulation of the components which rely on it. As an example, if earnings are under-reported in the survey, not only will social insurance contributions be under-estimated, but so will be the size of any tax relief on the contributions. Income taxes will be over-estimated for this reason, but at the same time under-estimated because of the under-reporting of earnings. The problem with earnings under-estimation may seem less serious than it is, because of the under-estimation of the tax relief.

The discussion and interpretation of the macro-validation comparisons is one of the most important parts of the Country Report. Where possible, reasons for discrepancies are given and otherwise their potential causes are discussed, taking the specific country context into account.

3.1.2 Data issues

Estimates do not always match well for a wide variety of reasons, including most fundamentally due to the input data not being perfectly representative of the population, and not containing the precise information that is required for simulations.13 one important example is provided by the harmonisation process that the EU-SILC User Database (UDB) undergoes before its release by Eurostat which involves the aggregation of income components into combinations provided as single variables. This results in loss of information that is needed by EUROMOD: the detail of national benefits, pensions and other income sources according to the national design. One of the main country-specific tasks involved in deriving the input dataset for EUROMOD is reconstructing some or all the original variables. This is only unnecessary if all the components can be fully simulated by EUROMOD or if none of them can and they are all treated in the same way by the rest of the tax-benefit system. The simplest solution leading to the highest quality results is if it is possible to combine the disaggregated components from the national version of the EU-SILC with the UDB. This is only possible if (i) the two versions of the data have the same (or can be record-linked) IDs, (ii) the national SILC data are made available by the National Statistical Institute (NSI) for this purpose, and (iii) the disaggregated variables are included in the national SILC dataset and are consistent with the UDB harmonised variable. An alternative solution is to use the national SILC dataset instead of the UDB, if this is available. If neither of these solutions is possible, usually because the national data are not made available for this purpose, then the individual components of each harmonised variable must be imputed, using whatever information is available.14

From 2014 onwards, the Eurostat UDB SILC has included, for a growing number of countries, the harmonised benefit variables each disaggregated into four sub-components, defined using the two two-way European System of Integrated Social Protection Statistics (ESSPROS) categories of non means-tested/means-tested and contributory/non-contributory. This disaggregation, together with metadata describing which national variables are included in which disaggregated variables, is intended to make the imputation of components more straightforward and more precise (because the number of components in the new harmonised variables will usually be smaller than in the old).

The data imputation processes and their validation are documented in EUROMOD Country Reports but it is undoubtedly the case that the quality of the imputations is lower than that of the variables provided directly, although it should be noted that in some cases imputations based on detailed external data may validate quite well.

3.1.3 Other issues

Further reasons for the basic baseline simulations not matching external statistics include noncompliance with the policy rules (tax evasion and benefit non-take-up), the additional challenges associated with making detailed forward projections, and conceptual mismatches between simulated estimates and external statistics. These are discussed in turn.

Tax evasion and non-take-up of means-tested benefits may result in simulated estimates of the instruments being too large in relation to administrative statistics, if no adjustments for these phenomena are made. Adjustments are made in EUROMOD when there is evidence available to base them on. Even then, they are necessarily approximate. It is also possible for the user to switch them off, assuming full compliance, if desired. These adjustments are documented in Country Reports and the cross-country picture is summarised in an annual report on the baseline statistics, the latest of which is Tammik (2018).

As described above, the main macro-validation exercise is carried out for the policy year corresponding to the data income year (for instance, 2014 using 2015 EU-SILC). However, EUROMOD provides policies up to the year current at the time of release and the results for these later systems, using projected data (for instance, 2014 incomes from 2015 data, projected to 2017), are also validated and two additional issues are encountered. First, suitable external statistics, especially for the most recent year, may only be available with some delay. Secondly, the projection itself is subject to some error. Input data are projected forward to a recent or current policy year by inflating income sources using specific indexes (see the Country Reports for detail and EUROMOD (2018b) for the principles behind these adjustments). Given the aggregate nature of this type of adjustment, it will not typically capture variations in the growth of non-simulated income components by personal or other characteristics. In addition, adjustments for changes in population characteristics (for instance, labour market, demographic, household composition) between the data collection year and the policy year (if different) are not generally made. Users are free to re-weight the data to make their own adjustments, if required. Lack of adjustment for compositional changes in the population may introduce additional error to some degree. Studies aiming to “nowcast” the income distribution across the EU have used dynamic microsimulation techniques with EUROMOD to adjust for labour market changes (Leventi, Rastrigina, Sutherland, & Navicke, 2017; Navicke, Rastrigina, & Sutherland, 2014) or a mix of these and re-weighting.15 These studies include validations of the approaches by comparing nowcast estimates of median income and at risk of poverty (AROP) with what later releases of the EU-SILC eventually show.

Finally, the appropriate external statistic depends on the particular interpretation one wishes to put on the EUROMOD estimate, and how this estimate is computed. For example, in assessing the quality of baseline estimates of income tax by comparing against other estimates there are at least three possibilities, depending on the purpose of the analysis. The first is to match administrative statistics derived from the process of the collection of income tax, so (ideally) taking into account evasion as well as avoidance in the simulations. The second is to measure income tax liabilities, assuming full compliance within the reporting period, which would typically imply a larger amount than captured by tax administration statistics, but which is difficult to validate due to lack of external information. The third possibility is to estimate the amount of tax paid as captured by the input data, which is relevant when “nowcasting” what the data will show once they are available for the current period (Leventi et al., 2017). This would need to take account of misreporting in the micro-data collection process which is not necessarily the same as misreporting to the tax authorities (Paulus, 2015).

3.2 Scope of simulation

Scope here refers to the amount of policy that is simulated. Firstly, we can consider this in relation to the main purpose of a model like EUROMOD: the proportion of direct taxes and cash benefits and pensions included in the concept of household disposable income that can be simulated, as opposed to taken from the data. “Policy scope” can also be considered with reference to changes in the full extent of public policy (including indirect taxes, provision of non-cash services like health and education, public goods more generally, effects of regulation, for instance, of rents, etc.) or factors largely beyond public control or responsibility such as company pay policy. The fact that models may be adapted to extend the scope of the policies that can be simulated beyond policies directly affecting household disposable income (and in public control) adds further complexity to the definition of what is being assessed for quality. It highlights the importance of having a clear statement of the purpose of the model, before designing its quality assessment.

Clearly, the more policy that is simulated the more useful is the model. What is possible depends on the input data which means that scope is country-specific because data needs of policy systems differ. Differences in scope can reduce comparability of results across countries (see Section 3.3 below). While there is potential to improve policy scope with imputations and extensions to the input data, there is a trade-off between policy scope and quality in other dimensions because imputations with little information to base them on may simply introduce error.

3.2.1 EUROMOD practice

EUROMOD aims to simulate as much as possible of the public policy system that has a direct impact on household disposable income, plus employer social insurance contributions. More specifically it aims to include all social insurance contributions, income taxes, property, wealth and other personal direct taxes (where possible, but not taxes on capital gains or capital transfer), cash benefits and pensions, and the minimum wage rules. As much disaggregation as possible is maintained (for instance, social insurance contributions by function, if relevant); as much detail as possible is captured (for instance, specific tax deductions); and regional variation is included, where possible. Typically, contributory benefits and pensions cannot be simulated because of lack of information on contribution history and/or scheme membership. similarly, benefits that depend on a medical assessment, such as disability benefits, cannot be simulated either.

However, some of these benefits and pensions, together with some other components that depend on missing information can be “part-simulated”. Typically, this means using receipt of the benefit in the data as a proxy for their eligibility conditions, with some other features, such as levels of payment, being simulated with parameters which can be changed by the user.

Country Reports explain which elements of the national systems are simulated, part-simulated or not simulated and simply taken from the data, and, in the latter two cases give reasons why they cannot be fully simulated. In the case of “full” simulation where assumptions have to be used in the absence of particular pieces of information, these assumptions are explained too. In addition, unemployment benefits (contributory as well as non-contributory) are simulated in all countries. They are used in the baseline if their macro-validation suggests they are a good reflection of what administrative statistic show. Otherwise the simulations are only used in the recalculation of incomes for the construction of replacement rates related indicators for those observed in the data to be in work.

As well as the full details in the Country Reports, the EUROMOD output statistics provided online also include notes identifying which elements of the system are simulated or taken from the data.16 The broad pattern of which types of benefits/pensions and taxes/contributions can and cannot be simulated is quite similar across countries, with some exceptions. But this does not necessarily result in a uniform proportion of the whole system being simulated across countries. For example, in countries with a greater reliance on contributory benefits and/or large pension systems, a lower proportion of the total benefit/pension expenditure tends to be simulated. Such issues need to be considered when interpreting results from EUROMOD, and when assessing comparability across countries, which is the subject of the next section.

3.3 Cross-country comparability of results

Cross-country comparability of results is a dimension of quality that is of particular relevance to EUROMOD. It is not straightforward to establish. Focussing on baselines, and existing policy systems, there is the possibility to compare the relative validity of results across countries. If one country has a strong assessment and another a weak one, this might suggest a lack of comparability but this does not necessarily follow since it depends on particular use of the model. However, the interpretation of comparisons across countries is aided by country-by-country documentation available with standardised format and content, as is provided in the Country Reports. In general, comparability cannot be established by looking at the results and must be assessed through qualitative examination of inputs, protocols and processes intended to ensure comparable treatments. This means that protocols and processes must be documented and their implementation in practice monitored and reviewed. However, it should be clear that comparability of results does not necessarily result from nor require doing identical things for each country. This is because some features may be more important in some countries than in others.

3.3.1 Data issues

Making use of input data that are derived from a data source that has been harmonised across countries, as in the case of the EU-SILC, is clearly of great benefit in facilitating a common approach. This is due not only to the benefit of a common data structure but also a common data access permission process and the synchronised release of data. The importance of these dimensions of convenience should not be under-estimated in the context of so many countries.

Nevertheless, the specification of the content of the EU-SILC as well as the harmonisation process may meet the data input requirements of EUROMOD in some countries better than in others. This is because different policy systems have their own specific information requirements and the harmonisation process will obscure or reveal these requirements to varying extents. Where alternative national input data are available and are better suited than the EU-SILC then single country quality criteria need to be balanced with —and are in practice prioritised over— any desire for strict comparability of inputs across countries. In fact variables from national versions of the SILC are used in 8 out of 28 EU countries in EUROMOD.17

3.3.2 EUROMOD practice

EUROMOD procedures for maintaining comparability across countries are explained in a document called “EUROMOD Modelling Conventions (EMC)”. This sets out guidelines and protocols for building and updating a country in EUROMOD, with the idea that all countries should comply with all guidelines.18 It is reviewed annually, taking account of any new issues faced in the most recent update. While this document is intended as a guide for those developing the model, it is also a useful resource for users wanting to understand the assumptions and adjustments that lie behind the model. It covers guidelines for the following aspects:

Input datasets: this is a general guide; there are also Stata do-file templates and the Data Requirements Document (DRD) which documents how variables have been derived in each country’s input data. The latter is made available to EUROMOD users along with the input micro-data.

Variable naming convention.

How to derive and document the indexes used to update monetary variables that are not simulated from the data collection year to the policy simulation year.

System and data configuration.

Scope and date of policies to be simulated.

Order and structure of policies.

“Policy switches”: it is here that benefit non-take-up and tax evasion switches are explained, along with other on-off switches, and their status in the baseline simulations.

Standard assumptions for simulating two policies that pose specific but varying challenges across countries: unemployment benefits and minimum wages.

Rules for defining EUROMOD “tax units” (assessment units) and “income lists” (aggregations of income components).

Output variables.

An explanation of how to do standard EUROMOD macro-validation.

3.4 Validity of estimates of the effects of policy and other changes

The main purpose of a tax-benefit microsimulation model such as EUROMOD is to assess the effects of changes. The changes of interest may be actual changes in policy (see for instance Bargain (2012) for particular UK government’s reforms; Paulus, Figari & Sutherland (2017) for eight countries over the post financial crisis period) or alternatively hypothetical changes intended to inform the design of specific reform proposals or draw out the implications of new policy designs (recent examples include Anthony B. Atkinson, Leventi, Nolan, Sutherland, & Tasseva, 2017; Browne & Immervoll, 2017; Figari et al., 2017) or “policy swaps” across countries (Popova, 2016; Salanauskaite & Verbist, 2013). In the case of hypothetical reforms there are almost unlimited possibilities and it is not possible to provide an ex ante assessment of the quality of results across the full range. This is something that users must do for themselves.

The “what if” functionality of tax-benefit microsimulation models can also be used to capture the implications of other changes on the effects of tax and benefit policies. These may be macroeconomic, demographic, household compositional or labour market changes, often simulated in a stylised manner. Whether the point is to assess the micro (individual)-or macroeconomic stabilising effects of the tax-benefit system (Dolls, Fuest, & Peichl, 2012; Fernandez Salgado, Figari, Sutherland, & Tumino, 2014), the work incentive or labour supply effects of tax-benefit systems (Ayala & Paniagua, 2018; Bargain et al., 2014; Collado, 2018; Jara Tamayo, Gasior, & Makovec, 2017) or the effects of demographic change on the fiscal balance (Dolls et al., 2017), the quality assurance of the tax-benefit calculations from EUROMOD rests on their documented validation when applied to baseline data (see Section 3.1 above). However, as mentioned there, this may be a misleading guide to the quality of simulated changes if the baseline has been calibrated, in a hidden way, to match external control variables. It is therefore important that the user has access to information about such calibrations as well as the means to amend them to suit their own application.

In the case of actual policy changes there may be more evidence to work with. There may be official estimates of the effects of high profile specific changes. Some EUROMOD Country Reports, when discussing changes in the macro-validation assessment from year-to-year when there have been policy changes, take into account external estimates of the cost and numbers affected, where these exist (for instance, produced by the ministries responsible for the reform). Typically, however, these will themselves have been generated using a microsimulation model. Cross model comparisons are only helpful for quality assessment if one model has clear advantages, for example if it is based on a large sample of administrative data. Often there is no superior model available (if there is then it is unclear why it is not being used instead!). At the same time, cross-model studies can illuminate which assumptions and choices of method give rise to salient differences in estimates of the effects of changes within a particular context. For example, De Agostini, Hills, & Sutherland (2017) compared EUROMOD results for the UK with published estimates from two other respected national models, finding that most of the differences in results could be attributed to differences in assumption and analytical choices made by the model users, rather than the models themselves.19 This highlights the need for model users to be transparent about their assumptions and choices.

A description of the effects on household disposable income of changes between policy systems year-to-year is provided in the Country Reports. This is shown graphically, and in a table, as the percentage change in income for each household income decile group, as well as for the population as a whole, and is broken down by type of tax or benefit. An accompanying commentary explains which specific policy changes (or lack of changes: the calculations assume a counterfactual indexation by CPI) are responsible for the picture shown. While this analysis does not provide hard evidence that the effects of changes in policies are simulated accurately, it is a powerful plausibility check since national experts (authors of the Country Reports) as well as the Essex EUROMOD development team are involved in explaining the changes. An annual publication gathers the 28 analyses of “policy effects” together and adds a comparative perspective (EUROMOD, 2018a).

4. Use of EUROMOD

The extent, breadth and quality of use of EUROMOD can be considered as indirect “outcome” indicators of the quality of the model itself. In fact there is a “virtuous circle” operating, whereby the many users and uses of EUROMOD contribute to the identification and correction of bugs and errors in the model, and to suggestions for improvements. This in turn leads to better quality as well as a clear motivation for continuing to make EUROMOD openly accessible. In this short section we summarise available evidence on the numbers of users and uses.

4.1 Users

Table 1 shows the evolution of the number of registered users for each release of EUROMOD that is made generally available. EUROMOD has been made generally available in some form since 2002 but it is only since 2011, when version F3.0 covered 18 countries only, that access has been properly supported and systematically recorded.

EUROMOD users by release and type of institution.

| Release | F3.0 | F5.0 | F6.0 | G1.0 | G2.0 | G3.0 | G4.0 | H1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Feb11–Dec11 | Dec11–Aug12 | Aug12–Aug13 | Aug13–Aug14 | Aug14–Feb16 | Feb16–Dec16 | Dec16–Dec17 | Dec17–Feb18* |

| Universities and research institutes | 28 | 35 | 36 | 62 | 114 | 97 | 97 | 49 |

| Public administrations | 2 | 2 | 7 | 15 | 23 | 28 | 41 | 13 |

| European Commission | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 15 | 22 | 9 |

| International organisations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 2 |

| Total | 31 | 38 | 46 | 85 | 163 | 167 | 180 | 76 |

-

*

Notes: Latest information; these figures refer to the first 3 months of the release being available.

These figures give a broad indication of the extent of use, how it has grown over recent years and the category of institutional affiliation of individual users. It does not include registered use of spinoff models for non-EU countries after the first access to the platform by those constructing these models.

4.2 Uses

Papers using EUROMOD are published in the EUROMOD Working Paper series and the number of papers per year (up to March 2018) is shown in Figure 2.

Working Papers are subject to some quality control and a light editorial process. Many of them go on to be published in peer-reviewed books and academic journals. The journals in which papers using EUROMOD have been published to date include: Annals of Economics and Statistics, Baltic Journal of Economics, Basic Income Studies, Brussels Economic Review, Cambridge Journal of Economics, CESifo Forum, Eastern Economic Journal, Economic Journal, Economic Policy, Economic Thought, Economica, Economics Letters, Empirica, Energy Policy, Financial Theory and Practice, FinanzArchiv, Fiscal Studies, Intereconomics, International Journal of Microsimulation, International Journal of Social Welfare, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, International Tax and Public Finance, Italian Economic Journal, IZA Journal of European Labor Studies, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, Journal of Common Market Studies, Journal of Comparative Economics, Journal of Economic Inequality, Journal of European Social Policy, Journal of Human Resources, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Journal of Policy Modeling, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, Journal of Public Economics, Journal of Social Policy, Journal of the Economics of Ageing, Labour Economics, Labour: Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations, Lithuanian Journal of Statistics, Norwegian Journal of Welfare Research, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Oxford Economic Papers, Political Studies Review, Public Finance Review, Public Sector Economics, Review of Economics of the Household, Review of Income and Wealth, Revue Franyaise d'Economie, Social Choice and Welfare, Social Indicators Research, Social Policies, Social Policy and Administration, Social Policy and Society, Social Science Computer Review, South European Society and Politics, Theoretical and Applied Economics.

However, not all uses of EUROMOD are published in academic outlets. EUROMOD is increasingly used by public administrations and international organisations to inform the policy process as well as policy analysis (see Table 1). Some recent highlights include:

EUROMOD is used to assess the impact of policies as part of the European Semester process. In the 2017 country reports it was used in 10 different countries (Denmark, Spain, France, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden) and it is expected that use will grow to cover most countries in the future.20

Eurostat relies on EUROMOD to produce “flash estimates” of income distribution for the EU, publishing, in collaboration with Essex, experimental statistics for the first time in 2017.21

Analysis using EUROMOD is increasingly used by European Commission services, appearing regularly in both DG-EMPL’s annual publication Employment and Social Developments in Europe and the DG-TAXUD/DG-ECFIN annual report Tax Reforms in EU Member States.22 The 2017 Report on Public Finance in European Monetary Union includes analysis using EUROMOD on the impact of fiscal policy on income distribution and the influence of institutional factors on public investment in the EU.23

Many uses, including some original analysis as well as citations, in the OECD’s “In It Together. Why Less Inequality Benefits All”.24 OECD also used EUROMOD in its recent work on Basic Income.25

Analysis using EUROMOD provided an important part of the evidence base for a 2014 IMF report on Fiscal policy and Income Inequality.26

There are also studies on individual countries, produced by, or for, their public administrations. For up-to-date information on these, as well as the most recent published uses by international organisations, the reader is invited to refer to the EUROMOD website.

5. Conclusion

Assessing the quality of microsimulation models is important if their use in both academic and policy environments is to be justified. EUROMOD has a long-standing tradition of being openly available and has the largest country coverage of any model of its kind. It has highly-developed and well-embedded protocols and practices aimed at ensuring high quality results. This paper has explained how the quality of EUROMOD is assessed, and this assessment made available, with the aim of passing on useful lessons —in the spirit of openness and transparency— to the institutions taking over responsibility for the model’s maintenance, as well as the wider microsimulation community.

We have seen that there are some important trade-offs between quality in different dimensions. First, a model that is shown to capture the effects of taxes and benefits on the household income distribution in an accurate and precise way in the baseline may not measure the effect of changes so well (and the reverse may alternatively be the case). Calibrations and adjustments that force baseline results to match some external requirement (such as National Accounts aggregates) may distort distributions of relevant baseline variables to the extent that the effects of changes are less well captured than without the calibration. Secondly, broadening the policy scope of simulation and hence the questions that can be addressed by the model, must be balanced with the quality of the estimates that may be achieved using extensive imputations and assumption. Thirdly, comparability of results across countries may be to some extent at odds with maximising quality in any one country, given the different tax-benefit policy systems and their varying requirements from the input data (and, potentially, varying quality of input data). This trade-off between quality and comparability is one key aspect of appreciating how to assess the quality of EUROMOD.

The right balance in all these cases depends on the question at hand. This illustrates how a quality assessment for one purpose may not be generally applicable and that much of the responsibility for relevant quality assessment of results from EUROMOD necessarily rests with the users of the model rather than its developers. The responsibility of the developers is to provide in the public domain (i) basic quality assessments that are fully documented, explained and the results interpreted, (ii) information on the principles and processes involved in constructing the model, including the approach to key trade-offs between different dimensions of quality, and (iii) transparency when assumptions have been made or there are choices for the user.

The first step in any quality assessment of a microsimulation model is to define the purpose of the model. This statement of purpose can be seen as an important component of a comprehensive quality profile. In the case of a multi-use and multi-user model, such as EUROMOD, this is not straightforward to define, since new unanticipated applications may always be developed. Nevertheless, Section 2 of this paper includes an attempt to describe the purpose of EUROMOD. The trade-offs are (deliberately) not all resolved by EUROMOD’s developers and many choices can and should be made by the user. Thus some of the dimensions of quality that are particularly salient in the case of EUROMOD may be those not considered in any detail here, such as its transparency, flexibility, timeliness and the user experience in general. Assessment of these is the subject of further work, as is EUROMOD itself.

Footnotes

1.

A phased process which began in 2017 and is expected to be completed by 2021. See https://www.euromod.ac.uk/2017/09/26/european-commission%E2%80%99s-commitment-euromod.

2.

3.

4.

5.

For more information see https://www.euromod.ac.uk/using-euromod/access/data-permissions.

6.

These adaptations have been applied for one country, several or all, depending on data availability. It should be noted that not all of them are made generally available.

7.

A project in collaboration with UNU-WIDER and SASPRI, see https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/southmod-simulating-tax-and-benefit-policies-development.

8.

These models use the same software, structure and general approach, but they are not necessarily comparable in other ways. Using them as the first foundations of “WorldMOD” for global comparisons and analysis, for example, would require additional effort to align concepts, assumptions and —especially— data.

9.

Quality Reports for the EU-SILC can be found at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions/quality/eu-and-national-quality-reports.

10.

the EUROMOD “baseline” refers to results based on an actual policy system and the input dataset that is the closest in time, as well as using the set of standard EUROMOD assumptions. See EUROMOD (2018).

11.

For more discussion see Figari et al. (2015), page 2186.

12.

See https://www.euromod.ac.uk/using-euromod/country-reports. As well as the most recent Country Report for each country, past editions are available, going back as far as 1998 for many of the EU15 countries.

13.

Sample size limitations also affect the statistical reliability of comparisons.

14.

In some cases national SILC data are made available to EUROMOD’s developers only to inform the imputation strategy, not for access by users.

15.

16.

https://www.euromod.ac.uk/using-euromod/statistics. See the notes below each table in the country tabs. The statistics themselves report on the proportions of taxes and benefits in each country that are simulated.

17.

This figure is for the 2015 data. It includes the UK for which the Family Resources Survey is used. These are the national data underlying the UK SILC 2012–16. The use of national variables can change over time depending on changes in the national data access arrangements as well as the need for the variables as policies evolve. This illustrates how strict comparability over time may be traded against prioritising quality at any one point in time.

18.

19.

In fact, one of the main differences was in the detail of the policy changes that were included in the modelling! It is not possible to tell in all cases whether this was based on quality considerations (for instance, some policy changes were not possible to simulate in the model with sufficient precision or at all) or was the choice of the analysts concerned.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

References

-

1

Improving income protection for the elderly poor in Ecuador (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM2/18)Improving income protection for the elderly poor in Ecuador (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM2/18).

-

2

The Global Distribution of IncomeIn: AB Atkinson, F Bourguignon, editors. Handbook of Income Distribution. Elsevier. pp. 937–979.

-

3

Reducing poverty and inequality through tax-benefit reform and the minimum wage: the UK as a case-studyJournal of Economic Inequality 15:303–323.

-

4

The impact of tax benefits on female labor supply and income distribution in SpainReview of Economics of the Household.

-

5

TREMOD: a microsimulation model for the Province ofTrento (Italy) (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM15/14)TREMOD: a microsimulation model for the Province ofTrento (Italy) (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM15/14).

-

6

The Distributional Effects of Tax-benefit Policies under New Labour: A Decomposition ApproachOxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 74:856–874.

-

7

Comparing Labor Supply Elasticities in Europe and the United StatesJournal of Human Resources 49:723–838.

-

8

Dynamic scoring of tax reforms in the European Union (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM14/17)Dynamic scoring of tax reforms in the European Union (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM14/17).

-

9

Mechanics of replacing benefit systems with a basic income: comparative results from a microsimulation approachJournal of Economic Inequality 15:325–344.

-

10

Financial work incentives and the long-term unemployed: the case of Belgium (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM1/18)Financial work incentives and the long-term unemployed: the case of Belgium (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM1/18).

-

11

EUROMOD extension to indirect taxation: final report (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 3.0)EUROMOD extension to indirect taxation: final report (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 3.0).

-

12

Were we really all in it together? The distributional effects of the 2010 – 2015 UK Coalition government’s tax-benefit policy changes: an end-of-term update (EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM13/15)Were we really all in it together? The distributional effects of the 2010 – 2015 UK Coalition government’s tax-benefit policy changes: an end-of-term update (EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM13/15).

-

13

Fiscal sustainability and demographic change: a micro-approach for 27 EU countriesInternational Tax and Public Finance 24:575–615.

-

14

Automatic stabilizers and economic crisis: US vs. EuropeJournal of Public Economics 96:3–4.

-

15

EUROMOD Hypothetical Household Tool (HHoT) – User manual (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 4.0)EUROMOD Hypothetical Household Tool (HHoT) – User manual (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 4.0).

-

16

EUROMOD Modelling Conventions (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 1.1)EUROMOD Modelling Conventions (EUROMOD Technical Note No. EMTN 1.1).

-

17

Effects of tax-benefit policy changes across the income distributions of the EU-28 countries: 2016-2017 (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM4/18)Effects of tax-benefit policy changes across the income distributions of the EU-28 countries: 2016-2017 (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM4/18).

-

18

Welfare compensation for unemployment in the great recessionReview of Income and Wealth 60:S177–S2014.

-

19

Approximations to the Truth: Comparing Survey and Microsimulation Approaches to Measuring Income for Social IndicatorsSocial Indicators Research 105:387–407.

- 20

-

21

Removing Homeownership Bias in Taxation: The Distributional Effects of Including Net Imputed Rent in Taxable IncomeFiscal Studies 38:525–557.

-

22

The use of hypothetical household data for policy learning – EUROMOD HHoT baseline indicators (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM6/18)The use of hypothetical household data for policy learning – EUROMOD HHoT baseline indicators (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM6/18).

-

23

Could a universalfamily payment improve gender equity and reduce child poverty in Australia? A microsimulation analysis (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/14)Could a universalfamily payment improve gender equity and reduce child poverty in Australia? A microsimulation analysis (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/14).

-

24

Towards a multi-purpose framework for tax-benefit microsimulation (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM2/01)Towards a multi-purpose framework for tax-benefit microsimulation (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM2/01).

-

25

An introduction to EUROMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Senes No. EM0/99)An introduction to EUROMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Senes No. EM0/99).

-

26

Low incentives to work at the extensive and intensive margin in selectedEU countries (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/17)Low incentives to work at the extensive and intensive margin in selectedEU countries (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/17).

-

27

Redistribution in a joint income-wealth perpective: a crosscountry comparison (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/18)Redistribution in a joint income-wealth perpective: a crosscountry comparison (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM3/18).

-

28

Nowcasting risk of poverty in the European UnionIn: AB Atkinson, AC Guio, E Marlier, editors. Monitoring social inclusion in Europe. Eurostat. pp. 353–363.

-

29

Micro-simulation in action: Policy analysis in Eurpe using EUROMODA short introduction to EUROMOD: An integrated European tax-benefit model, Micro-simulation in action: Policy analysis in Eurpe using EUROMOD, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

-

30

Increasing labour market activity of the poor andfemales: let’s make work pay in Macedonia (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM16/13)Increasing labour market activity of the poor andfemales: let’s make work pay in Macedonia (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM16/13).

-

31

Nowcasting Indicators of Poverty Risk in the European Union: A Microsimulation ApproachSocial Indicators Research 119:101–119.

- 32

-

33

Tax evasion and measurement error: An econometric analysis of survey data linked with tax records (ISER Working Paper No. 2015-10)Tax evasion and measurement error: An econometric analysis of survey data linked with tax records (ISER Working Paper No. 2015-10).

-

34

The design of fiscal consolidation measures in the European Union: Distributional effects and implications for macro-economic recovery. Oxford Economic Papers632–654, The design of fiscal consolidation measures in the European Union: Distributional effects and implications for macro-economic recovery. Oxford Economic Papers, 69, 3.

-

35

Constructing the tax-benefit micro simulation Model for Russia – RUSMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM7/12)Constructing the tax-benefit micro simulation Model for Russia – RUSMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM7/12).

-

36

Distributional impacts of cash allowances for children: A microsimulation analysis for Russia and EuropeJournal of European Social Policy 26:248–267.

-

37

Improving work incentives: evaluation of tax policy reform using SRMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM11/12)Improving work incentives: evaluation of tax policy reform using SRMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM11/12).

-

38

Is the neighbour’s grass greener? Comparing family support in Lithuania and four other New Member StatesJournal of European Social Policy 23:315–331.

-

39

EUROMOD: An integrated European Benefit-tax model. Final Rport (EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM9/01)EUROMOD: An integrated European Benefit-tax model. Final Rport (EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM9/01).

-

40

Multi-Country MicrosimulationIn: C O’Donoghue, editors. Handbook of Microsimulation Modelling. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 77–106.

-

41

EUROMOD: the European Union tax-benefit microsimulation modelInternational Journal of Microsimulation 1:4–26.

-

42

Baseline results from the EU28 EUROMOD: 2014-2017 (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM5/18)Baseline results from the EU28 EUROMOD: 2014-2017 (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM5/18).

-

43

Adapting EUROMOD for use in a developing country – the case of South Africa and SAMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM5/09)Adapting EUROMOD for use in a developing country – the case of South Africa and SAMOD (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM5/09).

-

44

NAMOD: a Namibian tax-benefit microsimulation model (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM7/14)NAMOD: a Namibian tax-benefit microsimulation model (EUROMOD Working Paper Series No. EM7/14).

-

45

SAMOD, a South African Tax-Benefit Microsimulation Model: Recent Developments (UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 2016/115)SAMOD, a South African Tax-Benefit Microsimulation Model: Recent Developments (UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 2016/115).

-

46

Updating NAMOD, A Namibian tax-benefit microsimulation model (UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 2016/143)Updating NAMOD, A Namibian tax-benefit microsimulation model (UNU-WIDER Working Paper No. 2016/143).

Article and author information

Author details

Acknowledgements

Preliminary ideas for this article were presented in a keynote address at the 6th World Congress of the International Microsimulation Association, Torino, Italy 21st June 2017. I am grateful for the discussions there. The process of maintaining and updating EUROMOD is financially supported by the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation “Easi” (2014–2020).

EUROMOD is a team effort and is only possible with contributions from 28 national teams and the members of the development team at the University of Essex, past and present. I am particularly grateful to the current members of that team for their help in putting this paper together. They are Paola De Agostini, Francesco Figari, Katrin Gasior, Xavier Jara, Jack Kneeshaw, Chrysa Leventi, Kostas Manios, Cara McGenn, Andrea Papini, Alari Paulus, Daria Popova, Miko Tammik and Iva Tasseva. Special thanks for helpful comments on an earlier draft are due to Francesco Figari, Alari Paulus, Iva Tasseva and the Editor. The usual disclaimers apply.

Publication history

- Version of Record published: April 30, 2018 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2018, Sutherland

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.